June 5, 2022

Japan is in a demographic sweet spot. In fact, I predict Japan will emerge as the one advanced economy that achieves the ultimate goal sought by policymakers — a new middle class will rise in Japan over the coming three to five years.

How so? Conventional wisdom suggests “demography is destiny.” On that basis, Japan’s economic fortunes appear to be doomed: every hour Japan’s population is dropping by about 70 people (1). As the baby boomer drag accelerates in the coming decades, the official prognostications suggests that in about 300 years, fewer than 300 Japanese may be left. So how can we be bullish about Japan?

Simply put, forecasts based on demographics are often more lazy arithmetics than real-world economics. Economic growth is never determined by population as such, but by the employment opportunities created for the people by entrepreneurs and their companies. China’s population has always been bigger and grown faster than Japan’s, yet the Chinese economy only started growing and creating prosperity when the Communist Party relaxed its grip and allowed citizens to seek better opportunities in the early 1980s. National income in general and domestic demand in particular goes up and down depending on how many people have a job and, more importantly, what kind of job they have or can realistically aspire to have. Here, Japan stands out among advanced industrial economies with the demographic forces now working to boost both the quantity and quality of employment.

The numbers speak for themselves: Yes, the Japanese population has been falling by about a quarter of a percent every year since hitting `Peak Japan` in 2009. But against this, actual employment has been rising steadily at a rate of 1 to 1.5 percent every year. So the drag from falling absolute population numbers has been more than offset by an increase in the number of people actually participating in employment and economic life. More and more Japanese have come out of unemployment or have re-entered the labor market. Statistically speaking, Japan’s total labor participation rate has risen by more than 5 percentage points over the past decade.

From here, there is still plenty of upside to sweat Japan’s human capital harder: Although now up to 85% percent, Japan’s total labor participation rate is still several percentage points below that of Sweden’s 89% or Switzerland’s 88%. In terms of quantity, this means more than 2 million people who are 15 to 65 year old are available to enter or re-enter economic life, if Japan moves up toward Swiss-level labor participation rates (2).

Chances are high that they will, because the driver here is the bare-bone economics of demand and supply. As the absolute supply of labor shrinks, companies are offering better terms of employment and higher pay, which in term prompts a positive supply response. People who were not prepared to work under the previous conditions are now willing and happy to re-engage with the economy under the new terms. Note that it is not just about higher wages. It is the total package of employment conditions that makes the difference between wanting to take a job or staying at home — job security, career development, work-life balance, etc.

From lost generation to new middle class

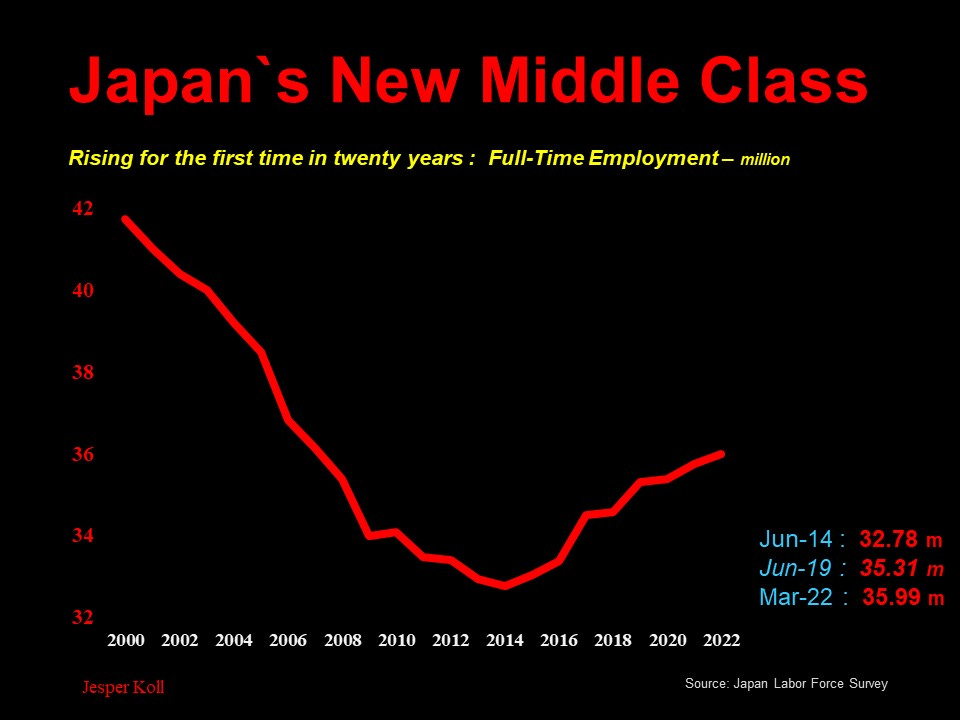

The positive change has already started. Japanese companies are now creating net full-time jobs. This is a complete reversal from what we saw during the previous 20 years — between 1995 and 2015, Japan Inc. was a net destroyer of full-time jobs. Part-time jobs were the only jobs created, which pushed up part-time employment from 20 percent to almost 40 percent of total employment between 1995 and 2015 (3). This was the death of ‘life-time employment’ and the birth of the ‘lost generation’.

However, about seven years ago this ‘lost generation’ dynamics began to change for the better. In 2015 full-time employment rose for the first time in twenty years. It has been rising ever since: full-time employment is up by 3.2 million people since it bottomed in June 2014 and March 2022, i.e. a 9.8% increase in the past seven and a half years. In fact, full-time job creation has consistently outpaced part-time one - since 2016, three out of four jobs created have been full-time.

Interestingly, during the pandemic, the newfound commitment to hire full-time actually accelerated: between June 2019 and March 2022, Japan Inc hired 680,000 new full-time employees.

To be sure, part-time employment was cut by 700,000 during the pandemic, so net corporate employment levels have basically been stagnant since June 2019. However, the data confirms anecdotal evidence from my company visits: many leading companies have begun to re-hire part-time employees on a full-time basis. Clear-speak: the quality of employment contracts has continued to improve during the pandemic (4)(and from here, the quantity of job creation is poised to pick-up as Japan’s service sector enters a post-pandemic and post-closed-country up-cycle).

Most importantly, Japan’s demographic destiny suggests this is a structural change that is here to stay. The war for talent will only intensify, forcing better and better contract conditions, rising incomes, greater job security, and better career prospects. This is how those potential 2 million Japanese will be incentivized to re-engage in the economy and why Japan is in a demographic sweet spot.

The power of the change in the quality of job creation — full time rather than part time — cannot be emphasized enough. It’s at the core of Japan’s virtuous economic up-cycle. First of all it directly boosts annual income by as much as 30 percent, not because of better benefits but primarily because a part-time employee is not eligible for the biannual bonus that full-time employees receive.

Secondly, a part-time employee has only limited access to credit, but the moment you become a full-time one, the credit spigot opens up. In fact, I use the consumer finance and mortgage credit data to verify or falsify my thesis: If I’m right and a significant cohort of Japanese people is now getting full-time jobs, the ability and willingness to borrow and buy a home should be rising. So far so good, with mortgage credit growth on a smart uptrend - something Japan has not experienced in basically one generation.

Of course, there are more positive multiplier effects in which a virtuous labor market cycle feeds a more virtuous and stable society. For example, household formation and marriage rates are now rising again. There is little doubt this is because of more diverse employment practices, better career opportunities and greater certainty of lifetime income stability. But it is not just labor, but also capital that benefits from the potential scarcity of labor. Japan’s corporations are now forced to completely rethink how to employ human capital, how to incentivize workers and managers, how to train and inspire their young and old.

Make no mistake — Japan’s demographics are forcing corporate Japan to become a global front-runner in designing a better future of work. In my personal view, chances are high that Japan’s private sector leaders and society will come up with an inspired solution, most likely something more human, more inclusive and better than the “geek” or “winner-takes-all” models of employment and labor incentives championed by so many American — and Chinese — economists and futurologists.

A corporate cultural revolution

The incentives and the pressure to do so is nowhere as real as in Japan. Here, the ‘war for talent’ is not just confined to software engineers or system integrators, but increasingly evident across all sectors. Japan’s labor market will become more and more of a buyers market, empowering the young, the able, and those previously excluded from access to a real career. This, in turn, will spark a positive reaction from employers. The growing fear of running out of talent will force corporate leaders to become more creative and innovative in order to attract and retain employees. Japan Inc. is poised for a true corporate cultural revolution. No matter how proud your corporate culture, how entrenched your HR process, how rigid your promotion ladder, how seniority-focused your career counseling and performance reviews, every day it becomes clearer that business as usual is no longer an option. If you don’t smarten-up your employee engagement, you’ll be running out of talent. If you don’t evolve your employment culture, you’ll be loosing your most important asset — human talent & ambition.

Already the top graduates of Tokyo University or Keio are more likely to go to a start-up than to a Keidanren Fortune 500 company. They are confident that should the start-up fail, they’ll still be in high demand, either from another start-up or from the establishment player they turned down before.

Already a leading company like Hitachi is struggling to attract Japan’s top engineers. The engineers have learned from their parents generation that established companies are just as untrustworthy as smaller ones to guarantee stable careers; and, more importantly, established larger companies reward conformity and continuity much more than creativity and innovation. In my experience of working with universities, start-ups, and established corporates, Japan’s new generation of engineers is very ambitious, wants to compete against Elon Musk, and is crying out for an opportunity to put into practice both, the ‘Kaizen’ (relentless focus on incremental improvement), demanded by traditional management priorities; as well as the disruptive innovation desired by the global market place and investors not afraid of funding high-risk, high-return projects & ideas.

It is a big mistake to expect Japan’s proud corporate- and social employment culture to turn into the hire & fire, winner-takes all, cutthroat competition model stereotypical American investors sometimes claim to prefer. Japan’s elite is simply too proud, too ambitious, and too pragmatic to give-in to something as self-obsessed, simple-minded and narrowly focused as Neo-liberal economic theory or libertarian societal ideals.

At the same time, it has always been wrong to assume Japan is too rigid, too inflexible, and too stubborn to change. Japan wants to - and will - create her own ‘new capitalism’. The primary driver is not the clever & opportunistic Prime Minister Kishida, but Japan’s relentless structural demographic destiny now making it imperative for private sector leaders to create a more productive, more inclusive and, dare I say, more happy and forward-looking corporate culture.

All this is, of course, the exact opposite dynamics of what Japan went through during the past thirty years when there was excess employment and an all powerful imperative to cut costs rather than invest in the future. More importantly, all this is exactly where productivity and prosperity comes from — human ambition demanding to be empowered.

All said, the economics of Japan’s population dynamics is not a negative force, but a positive one poised to deliver a sustainable uptrend in the purchasing power of the people, a new leverage and credit cycle, as well as a rise in overall productivity. Yes, Japan will sweat her human capital harder, will create more productive, more sustainable career- and employment practices. And as demographic destiny forces a new equilibrium between labor and capital, a new middle class will rise in tandem with a new corporate culture. Most importantly, the next generation of Japanese will be better off than their parents. You can see why I do want to be re-born as a 23-year old Japanese…

Thank you - as always, comments welcome. Many cheers ;-j

Next up from the Japan Optimist: if both the quantity and quality of employment has entered a virtuous up-cycle, why is Japanese consumer spending still stuck in the doldrums?

Notes:

In 2021, Japan`s total population dropped by 644,000 to 125.5 million.

See OECD Labor Force and Labor Force Participation data; almost two-thirds of the rise in Japan’s participation rate stems from ‘Womanomics’, i.e. rising female participation.

The term `part-time employees` here refers to all non-regular employees, which are the sum of temporary workers, Arbeito, Dispatched from agency, contract and entrusted employees. So anybody who does not have a regular employment contract. Source of data is the Labor Force Survey published monthly by the Ministry of Internal Affairs / Statistics Bureau of Japan.

In coming months, the quantity of job creation is poised to pick-up as Japan’s service sector enters a post-pandemic and, more importantly, post-closed-country up-cycle. I expect that the rise in full-time employment will accelerate with it, but this of course needs to be monitored carefully.

thank you for your note -- for starters I tremendously enjoyed "Japan 1941" by Eri Hotta ; "Embracing Defeat" by John Dower clearly sets the stage ; "How the conservatives rule Japan" by Nathaniel Thayer a classic must-read ; and always full of insights Nakae Chosen"s "a discourse by three drunkards on government" ; let me know your recommendations ; many cheers ;-j

What are your thoughts on the IMF's note on Structural Barriers to Wage Income Growth in Japan (https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/selected-issues-papers/Issues/2023/05/18/Structural-Barriers-to-Wage-Income-Growth-in-Japan-Japan-533515)? They argue that an additional boost to labour participation and incomes is constrained by the tax structure and disincentives for spouses to work beyond certain thresholds due to the income on both taxation and social benefits?