Go for it, Ueda-Sensei

Japan will not just end the world's last zero rate anchor, but will sooner rather than later begin to focus on containing rising inflation risks

The end is here. Since February 1999, the Bank of Japan has provided de-facto zero interest rate funding to Japan and the world. Now, Governor Ueda is poised to hike rates. One quarter of a century of `capitalism with a zero-cost rate anchor` is coming to an end. Sayonara Financial Socialism with Japanese Characteristics...

…and yes, Yokoso Inflation Made-in-Japan. Once rate hikes start, brace for an about turn in the public debate about monetary policy: how long before the Governor Ueda’s BoJ will be accused of doing ‘too little, too late’ to preserve the purchasing power of the Japanese people?

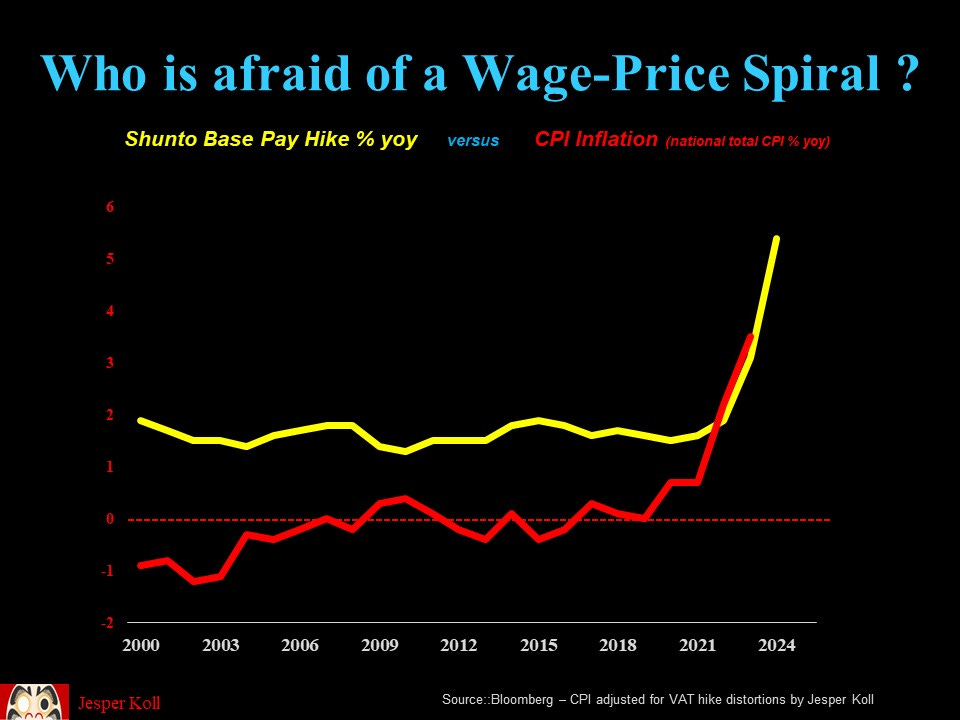

It’s painful for me to contemplate, but Japan’s inflation risk profile may be changing faster than I anticipated. What started two years ago with global supply- and terms-of-trade shock induced price increases is now on the cusp of turning into a potentially dangerous domestic wage-price-led demand-pull inflation spiral.

So, please Go for it, Ueda-sensei. Please make sure this Japan Optimist is wrong to contemplate a potentially pessimistic scenario – pessimistic for the real future purchasing power of the Japanese people, not Japanese asset prices.

At the very least, I think the time has come to be open to a complete re-think of how to assess Japanese monetary policy priorities: after the ‘lost decades’ of increasingly bolder actions taken to get out of deflation, slowly but surely the pendulum will swing towards policy actions specifically designed to reign-in inflation.

Fortunately for Governor Ueda in Japan ‘demand destruction’ policy levers can be pulled from both the monetary and the fiscal side. Japan does not suffer from parliamentary gridlock or populist leader dominated policy making - technocrats are in charge. Specifically, Japan’s next recession is more likely to be triggered by tax hikes than by Governor Ueda hiking rates too fast and to aggressively.

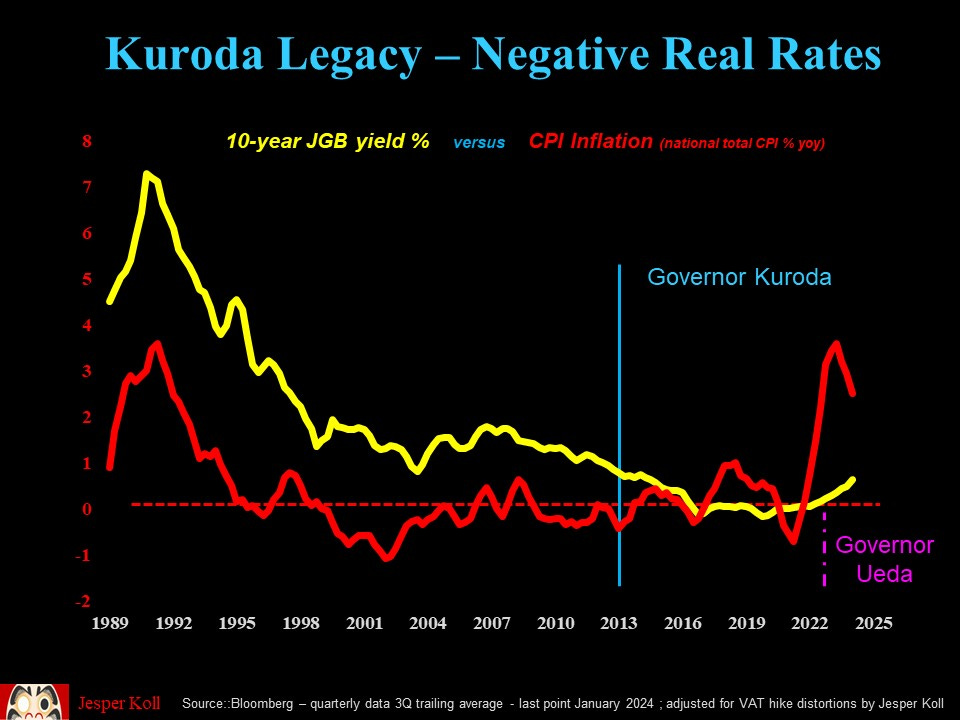

Practically speaking, I very much doubt Governor Ueda will break away from the true macro-economic legacy created by his predecessor Governor Kuroda: real policy rates are poised to stay negative for the foreseeable future. This should continue to support Yen risk assets - real estate, equities, and yes, non-Yen portfolio outflows.

Searching for the new normal

Make no mistake -- Ueda-Sensei does indeed face a heroic task: he must lead financial investors and real economy actors towards a new normal, away from decades of central-bank-led ‘emergency’ actions that did more to suppress debt-capital market price discovery than end deflation. Now that inflation is finally here, nobody has any idea where –or how-- Japanese inflation expectations will be anchored next.

After the BoJ consistently missed its stated 2% inflation target on the downside for almost three decades, private sector actors may be forgiven for not trusting the BoJ will now achieve it now that inflation has shot up to above the target. Yes, a first hike in rates will be presented as a vote of confidence that deflation has ended. But it does not follow that therefore inflation will be contained.

Fortunately, Governor Ueda knows better than anyone that he must be humble. I expect him to admit that, as he starts the journey towards normalization, he do not know what interest rate level is the optimal new normal neutral. This, of course, does not mean he is starting completely without references: apply the Taylor Rule to today’s Japan and you get a Taylor Rule Neutral Rate of slightly higher than 2% for the correct policy rate anchor.

No matter how theoretically sound, for all sorts of reasons there is no way for the BoJ to communicate and guide towards 2% when starting from zero -- it’s about 4-times above what market participants and forecasters expect (most economists currently expect a terminal policy rate anchor of around 0.5% in this cycle).

Instead, Governor Ueda is poised to stress a future rate path that is data dependent, that extra prudence will have an open mind, will focus on all sort of factors before deciding next steps. Strategic pragmatism, rather than new rules-based operational framework is is bound to be emphasized in the upcoming annual policy review. If, as I suspect, he is successful in his communications, Yen asset market volatility may actually decline.

Moreover, I expect Governor Ueda will also admit that he simply do not know what the likely impact of Japanese rate hikes will be on the economy and on markets. Prudence suggests economic models or benchmark reference elasticities must be mistrusted even more than usual given that :

a zero-cost policy rate anchor has never been maintained for such a long time - almost one generation of Japan’s commercial bankers, corporate treasurers and financial investors have never operated in a positive rate financial system or dealt with ‘normal’ upward-sloping yield curve. Make no mistake - completely new sets of behavior patterns and biases will have to be learned and evolve.

the deep structural changes that have occurred in both Japan’s capital markets and global financial linkages. At home, almost three-quarters of household mortgages are now floating rate debt, while in the last rate-hike cycle more than 80% were fixed-rate.

And never mind worries about the impact of higher rate on Japan’s record-high public sector debt levels: Japan’s total private sector non-financial debt – household- and corporate sector – is actually at an all-time high, 426% of GDP (here Japan leads the world - China is at 295%, the US at 264%, according to BIS data). A 50 basis point hike in interest rates would cost Japan`s private sector an additional Y11 trillion in interest expense, i.e. just about 2% of GDP.

Why not then?

Governor Ueda’s primary challenge will be to normalize Japanese monetary policy, without really knowing what normal is or how best to get there. It was his predecessor, Kuroda Haruhiko, who deserves to enter the history books as the BoJ Governor who’s actions and resolve completed the BoJ`s overarching mission until now - defeat deflation.

This old mission goal was formulated officially in April 1999 – two months after the overnight policy rate anchor was cut to de-facto zero (0.02%) -- when then Governor Hayami spelled out the BoJ’s overarching priority : ‘We are committed to maintain the zero rate anchor until the deflationary concerns are dispelled’.

Importantly, Governor Ueda was on then Governor Hayami’s policy board. By the summer of 2000, Hayami was convinced the economy was on a sustainable recovery path and, in August 2000, the policy board voted to abandon the zero-rate anchor that had been in place for 17 months. They hiked rates from zero to 25 basis points.

The vote was not unanimous: Ueda-sensei dissented.

History, of course, proved him right: it had been too early to abandon ‘ZIRP’ because not all channels of monetary transmission were working. Inflation expectations were not firmly anchored.

Barely three months after the August 2000 rate hike, Japan was back in deflation and, in one of the most embarrassing policy reversals ever, then Governor Hayami was forced to cut rates in February 2001 and, in March 2001 formally moved beyond ‘ZIRP’ by adopting the ‘quantitative ease’ framework. Governor Ueda was the key designer of both the academically rigorous justifications and the pragmatic operational tools needed to make this radical new policy credible and real.

Why now?

Until the end of last year, Governor Ueda went out of his way to stress that Japan’s future deflation risk profile is ‘asymmetric’, that the risks of a fallback to deflation were significantly higher than the probability of sustained inflation. He is, by nature, a very thoughtful and prudent man; but this does not mean that he is afraid of decisive action. When the facts change, the prudent man analyses and acts accordingly.

In my view, the facts have changed significantly, and with it the balance of risk: Deflation is not just over, but the probability of a potentially dangerous wage-price-led demand pull inflation spiral developing is now significant: all macro economic policy transmission channels are not just working but now point to potentially turbo-charging domestic demand-pull inflation.

And, more importantly, all policy parameters the BoJ has no control over – first and foremost Japan’s capital- and labor markets, but also Japan’s fiscal policy and FSA regulatory priorities – have turned decisively pro-inflation.

Specifically – first, the traditional macro channels

the credit channel – transmitting Central Bank pro-inflation policies into the real economy via on-lending, i.e. increased leverage: bank lending has been expanding steadfast at a 3-3.5% clip, now consistently expanding faster than national income growth for the first time in almost two decades.

This is a ‘leading indicator’ -- private companies taking on debt to fund the steadfast acceleration in domestic business investment will translate into future employment and future production. The just-completed-in-record-time TSMC / Sony chip factory in Kumamoto is but one example of a more general virtuous cycle – already a second factory is being committed to.

The case for continued acceleration in domestic CAPEX is a strong one: on-shoring, friend-shoring, labor shortages forcing capital deepening, Japan’s GX green energy supply grid policy targets and, last but not least, national economic security priorities forcing a newfound focus on domestic self-sufficiency in all things from food, to machine tools, to semi-conductors, to fighter-jets….

All said – domestic private sector demand for credit is rising, and Japanese banks are perfectly well capitalized to meet it without having to raise credit spreads: corporate balance sheets are also super strong. For the first time in over twenty years, Japan is in a genuine ‘boom’ phase of the credit cycle where supply- and demand for credit goes up, but credit costs don’t.

The wealth channel – asset markets in general, the real estate market in particular, are now consistently bid. Almost all regions in Japan now report steadfast increases in home and real estate prices. Even in Tokyo, apartment prices are now trading at new historic highs.

Real estate matters more so in Japan than America: 40.1% of household sector wealth is in real estate in Japan, compared to 32.3% in the U.S. So here is the real ‘feel good’ factor that, in many ways, is more important than the stock market (although I do acknowledge the ‘asset rich, income poor’ conundrum facing pensioners, particularly in rural Japan where possibilities to augment pension income by part-time employment are scarce).

The FX foreign exchange channel – the Yen has weakened consistently since the start of ‘Abenomics’, all the way down to levels last seen in the mid-1970s (on real effective exchange rate measures). This was the first of the classic transmission channels to become unclogged – and may very well become the first one to turn from pro-inflation support to neutral, or even ‘imported deflation risks rising’.

However, given Japan’s domestic CAPEX boom, industrial Japan ought to be in a much stronger position to withstand a Yen-appreciation induced loss of global competitiveness. Listed companies are budgeting their profit forecasts with a Y135-138/$ baseline, so there is some `yen strength` risk cushion. For the new financial year, corporate FX assumptions are poised to be even more conservative given the noise around BoJ rate hikes.

More importantly, at this stage, a modest Yen-strength induced improvement in Japan’s terms-of trade, i.e. import prices falling, will probably be a good thing, actually boosting private sector purchasing power and thus domestic demand. In my view, as long as the Yen does not surge back up towards, say Y115-120/$, the FX-channel will stay essentially demand-inflationary for both the economy and corporate profits.

Now the more important non-central bank policy parameters:

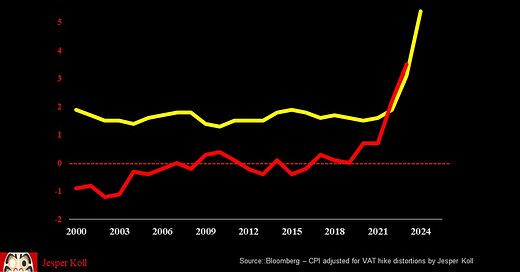

Labor markets have turned decisively inflationary. Here, the most current evidence is the annual `Shunto` base-pay negotiations yielding a 5.28% base pay hike. This is much stronger than the 3.5-4% expected by most experts just a couple of months ago. And yes, 5.3% is just about double the current inflation rate, and well above the 2% inflation target aimed for by the BoJ.

Now, remember that base-pay hikes were de-facto flat-lined around 1.5% for the past twenty years. Last year we went from 1.5% to 3.6%, and now 5.3%. Meanwhile, inflation went from de-facto zero over the past twenty years (ie. real base pay purchasing power rose of around 1.5%). Last year, inflation was 3.1% (ie. real base pay wages rose 0.5%); but this year inflation will run at just above 2% according to the BoJ policy board forecast, but the ‘Shunto’ just came in at 5.3%, ie. workers real purchasing power should rise by 3%, more than double the 1.5% average growth on the books for the past 20-years.

This obviously sounds great for domestic consumption. But the problem is this: the BoJ has zero control over the labor market in general, wage inflation in particular. And all indications are that Japan’s labor market will tighten further, that the skills mismatches will intensify and most likely compound to trigger an even higher ‘Shunto’ next year: the number of high-school and university graduates is declining, but the demand for specialized workers is rising. Locally, the gap could be filled by the retiring ‘Showa’ baby boom generation, but unfortunately these are mostly generalists who’ll need not just significant re-skilling but also greater pecuniary incentives to re-enter working life.

Clear-speak: why is this not the start of a wage-price spiral?

Meanwhile, the 5.3% rise in the ‘Shunto’ does also provide a welcome cushion against the potential rise on mortgage costs from higher rates: home affordability will now stay the same even if mortgage rates go up by as much as half-a-percent (at current average apartment prices in Tokyo).

Domestic capital market incentives have also turned decisively pro-inflation. The Stock Exchange new mandate to its members to show credible strategies and progress towards meeting their cost of capital and raising stock-price-to-book-values to above one is very inflationary: ‘lazy balance sheets’ being put to work, corporates sweating their assets will come in many forms and shapes, all of which are either asset- and/or demand inflationary.

Here it is important to remember Japan is more complex than the standard ‘at full employment’ macro models capture – Japan faces a structural downshift in the supply of labor. This means, for example, that labor-shedding triggered by a corporate merger does not, in the aggregate, lead to a rise in unemployment or a fall in wages; and all this on top of the reality where both male- and female labor force participation rates are already stretched at record high levels.

And one other consideration: one-in-four Japanese is now over the age of 70, i.e. increasingly likely to become more dependent on private- and public services rather than being able to supply them. Unfortunately, this is also inflationary – either the wages for service providers will have to rise, or the services provided will have to be rationed or cut-back; which is also inflationary in the same way that changing the packaging but reducing the number of potato chips inside the bag is – you pay more for less.

Debt capital markets in general, the JGB bond market in particular, have re-liquified smartly. This is Governor Ueda`s first concrete policy success: Governor Kuroda`s ‘bazooka’ of first stepping up aggressively BoJ bond buying in 2014 and then imposing a hard-cap of de-facto zero rates for the 10-year JGB yield in 2016 – aka YCC Yield Curve Control - resulted in an almost complete collapse of private sector liquidity in JGB markets. BoJ ownership of government bonds went from approximately 10% in 2013 to over 50% by the time Governor Ueda took over last year. The BoJ ‘crowded out’ private investors and, de-facto, nationalized Japan’s bond market.

But look what happened since: Governor Ueda`s first action was to raise the YCC cap to 1%, and then he abandoned the hard-cap ceiling. The 1% is now a reference rate, not a hard-cap ceiling.

The result is impressive: market functioning has been restored relatively quickly and the private sector has taken over as the primary source of liquidity and buyer of government debt.

Specifically: monthly government bond purchases by private investors fell from over Y30 trillion in 2013 to less than Y15 trillion by 2016; but since Governor Ueda took over, private purchases are back up smartly to just above Y30 trillion. He `liberalized` the JGB market. Importantly, never once did the 10-year JGB yield rise above 1% (it`s currently steady at around 0.7%). In other words, the private sector is perfectly capable of supplying liquidity, responding smoothly to free-market incentives and the central bank loosening its grip.

Team Ueda got this one very right.

Coordination with the Ministry of Finance (MoF) and the financial regulator (FSA) to prepare for a rate hike has been impressive, confirming that Governor Ueda is of no mind to change or re-neg the ‘Kuroda-Abe’ explicit agreement of close cooperation and ‘one voice’ coordinated economic policy making amongst MoF, BoJ and the Prime Ministers Office.

Specifically: MoF has budgeted for an increase in treasury financing costs from 1.1% in 2023 to 1.9% in 2024. So they are budgeting for a potential rate hike of 0.8%. Given that the average duration of Japan`s treasury debt is just inside of 6-years, this is a significant cushion against not just the end of zero-rates, but also against rate hikes.

One caveat – and potential trigger for more intense debate between MoF and Team Ueda in coming quarters - is the potential steepening of the yield curve: already, the policy-rate to six-year interest rate spread has risen from less than 10 basis points to around 45 basis points. Whether Governor Ueda’s actions from here will steepen the yield curve further or, potentially flatten it will thus become a key factor determining success or failure; and obviously not just from the MoF`s perspective.

Meanwhile, the FSA has issued new decrees and administrative orders with a focus on prudent loan-loss provisions and stepped-up stress-testing for portfolio impairment losses. Clearly, the end of zero-cost home-currency funding will raise any financial institutions portfolio volatility. Former FSA head and now deputy BoJ Governor Himino is taking no chances - you have been warned.

You can see why I think the time has come to be open for a complete re-think of Japanese monetary policy priorities: after ‘lost decades’ of trying to get out of deflation, now policy action may have to switch and focus on actually containing inflation. But before you get too excited about shorting JGBs, please remember that – unlike America or Europe -- ‘demand destruction’ in Japan can easily come from both monetary and fiscal policy.

In fact, for next year a modest tax hike is already planned: PM Kishida`s tax cut in the 2024 budget – every eligible Japanese person will get a check of about Y40,000 by the summer – is just a one-off. So in 2025, disposable incomes will take a hit (albeit small, barely 0.2% of disposable income).

More importantly, from the summer of this year, the Government Tax Council will begin its usual cycle of planning next year`s tax reform proposals. Already, some of the key members have floated trial balloons calling for `all options must be considered – hikes in corporate taxes, income taxes, consumption taxes. This is, supposedly, necessary to fund the new multi-year national strategic initiatives PM Kishida committed to – defense spending, regional revitalization, demographic decline countermeasures etc. Given the blow to the LDP delivered by the recent party funding scandals, MoF is poised to have an unusually strong hand in pushing a fiscal consolidation agenda.

We shall see. Personally I would expect it is more probable that Japan`s next recession is induced bytax-hikes, rather than Governor Ueda stepping on the brakes too fast or too aggressively. For now, however, what matters is that in the coming 6-9 months the relative easing of fiscal policy does create a unique opportunity for the BoJ to take first steps away from zero rates towards rate normalization.

Why give up the YCC?

One final point: This risk of a future fiscal tightening is one of the reasons why I do expect the YCC framework will be maintained – why give up a proven and very powerful policy tool when it does not cost you anything. As long as you set the YCC ‘reference rate’ above the likely free-market rate you’re not obstruction free market price discovery; but when you want to exercise control you can do so easily by forcing a flatter yields curve – YCC effectively gives the BoJ two policy tools, the standard short-term policy rate anchor and a long-bond potential cap. A tool that, when needed, allows to control the slope of the yield curve –and thus net interest margins for the banking system – is a good one to have, desho?

In an age where policy makers around the world are looking for more potential control against free market volatility and disruption, why would the BoJ relinquish a powerful policy tool that, under Governor Ueda’s leadership, has actually re-vitalized private liquidity provision and true price discovery. And it’s a nice zero-cost insurance policy – just in case the market gets overly worried about run-away inflation and the BoJ doing ‘too little, too late’.

Thank you for reading. As always, comments welcome. Greetings from almost-ready-for-Sakura Tokyo. Many cheers ;-j

More fascinating and highly-informed thoughts on the Japanese economy. Thank you for sharing.