Japan reality check #2: what is Japan's economy really good at?

Largest creditor to the world, full-time job creation at home, and an equitable distribution of wealth - what's not to like?

Last week, a Japanese business leader sent an email: “Jesper, I need your help. I am on my way to Davos and want to promote Japan. If you are to mention three good things about Japan’s economy with data, what would these be?”

Simple question. Here’s my answer:

1) Japan is the world’s largest creditor country

Total net assets owned by Japan - households, companies, government - stood at $3.2 trillion at the end of last year (1). This is 1.3-times more than the world’s number two, Germany. The true power of Japan is revealed by the fact that Japan has been the top global creditor for the past 31 years consecutive years.

Concrete: Japan’s public- and private banks have been the single largest creditor to IndoPacific countries for the past decade, consistently out-lending China by a factor of 3-5-times.

True: over the past 20 years, Japan’s public debt has doubled from approximately Y500 trillion to Y1,000 trillion. But at the same time, household savings also doubled, from approximately Y1,000 trillion to Y2,000 trillion. So for every Y1 added to the fiscal deficit, household savings went up by Y2. Add to this the relentless cash hoarding by private companies and you get the world’s largest creditor nation — more money earned than owed year-in and year-out for the past 31 years. A clear sign of strength.

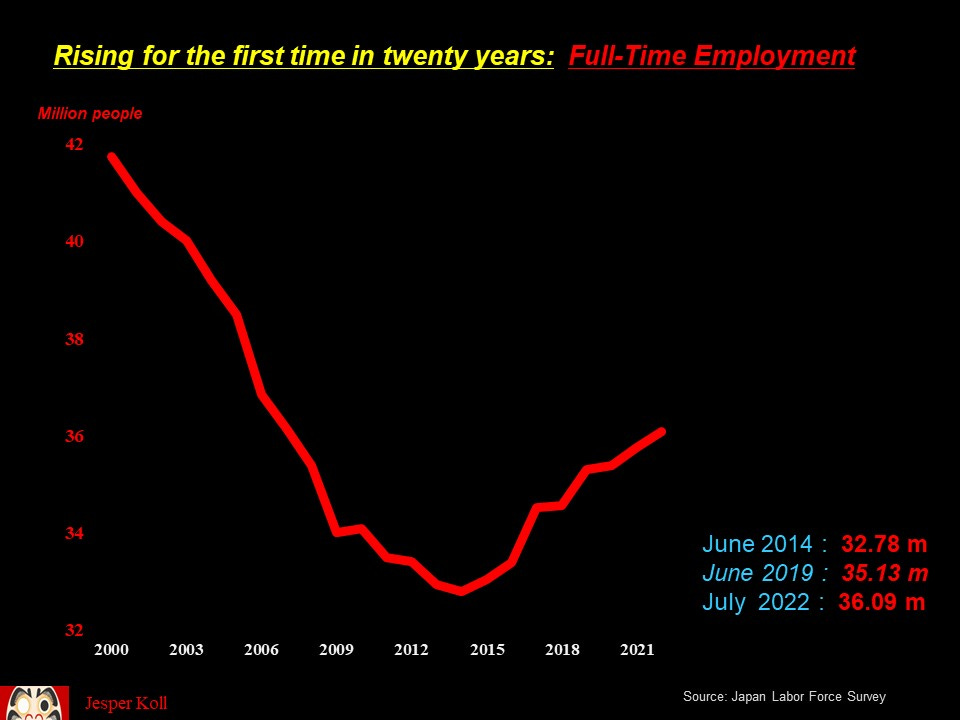

2) Japan’s domestic job creation machine is back at work

At home, Japan has created 2.6 million new jobs since 2016, and of these 2.3 million have been full-time jobs. The ‘lost decades’ — between 1996 and 2014 the only net jobs created were part-time — are over. Full-time jobs are the foundation of a new middle class, and in Japan a new middle class is now beginning to rise (2).

In addition to this positive inflection in the quality of employment contracts, Japan’s richest man and most successful entrepreneur, Yanai Tadashi, just announced a 40% pay rise for Fast Retailing employees. Of course, average wages will rise nowhere near as fast; but Fast Retailing’s move marks the starting gunshot in a ‘war for talent’ poised to intensify.

Who benefits?

First of all, the young generation will see a steady rise in its purchasing power, access to credit, and job security. They will be better off than their parents.

Second, the rise in employment costs is poised to start a cycle of “creative destruction”: the weaker “Zombie” companies finally are forced to close shop, thus freeing-up resources and market share for the top-performers. This is how Japan’s productivity will finally rise.

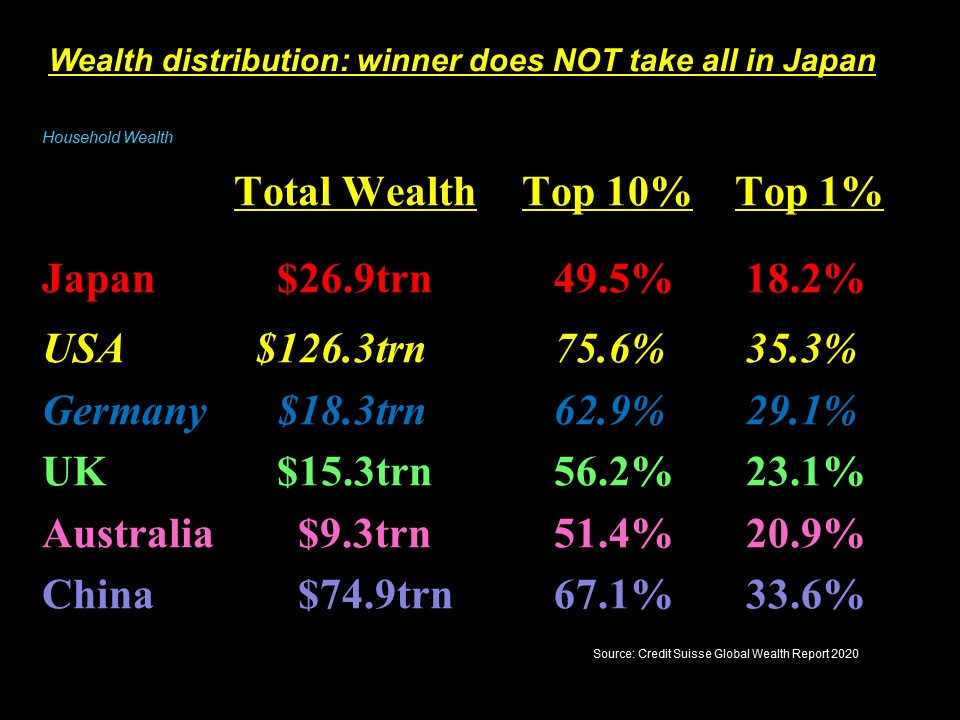

3) Japan’s wealth distribution is remarkably equitable

Japan is the richest country on earth, yet the top 1% own only just about 18% of the wealth. In contrast, both the American and the Chinese economies come across as much more “plutocratic”: the top 1% own 35% in “free market” America and 34% in “communist” China.

All said, Japan has remained very rich, is now creating high-quality full-time jobs, and has an inspiring track record of distributing wealth equitably.

Please let me know your own answer to my friend’s question. Thank you for reading & many cheers ;-j

P.S. : Food for thought

In many ways, Japan’s principal strengths are the classic economic virtues of:

thrift

job security (3)

equity

The opposite would be what used to be considered the classic vices of:

leverage

job violability

winner-takes-all

It has been fascinating to have witnessed over the past thirty years how Japan’s ruling elite has successfully upheld and promoted the classic virtues:

leverage was squashed in the aftermath of the bubble, with huge penalties imposed on consumer credit companies retroactively for all-of-a-sudden-deemed-excessive interest charges (although the high rates were perfectly legal at the time…). Before long, the consumer finance industry got rolled-up into the banks. Just before COVID, one of the major regional banks, Suruga Bank, got de-facto crucified for lending too aggressively to retail customers.

in late-1995, labor-laws were eased to allow part-time and contract workers in all industries, but the full-time job contract legislative framework was never touched or reformed.

although it is the global elites’ consensus opinion that the widening wealth- and income gap is undermining democracy, the late Prime Minister Abe remains the only G7 leader who actually raised top marginal tax rates in a meaningful way, from 45% to 55%.

There is a lot to be learned from Japan, because what actually went on over the past thirty years holds significant lessons for many national economies. Japan is not just well beyond the “lost decades”, but possibly well ahead of many nations looking for a better working model for their economies.

(1) end-2021 is the last available data point at the time of this writing.

(2) see details in this table:

(3) I am fully aware I’m on thin ice here from a strict economic theory perspective. Labor mobility is a hot topic. However, in the real world of Japan, the data confirms again and again that if you have a full-time, i.e. lifetime job, your chances of starting a family are 70-90% higher than if you’re a part-time or contract worker. If I’m right and full-time job creation accelerates further, family formation should pick up. More importantly, the baby birth rate is poised to rise. Let’s see…

Jesper, you make some good points but I can't agree with your premise that a failure to address meaningful labour market reform is a good thing. I would argue that lack of labour mobility is a key reason Japanese companies have been so slow to start raising wages notwithstanding much improved profitability and a tight labour market. Why pay more when there is little risk of people changing jobs (for full-time employees)? The rigid labour market continues to be an impediment to more efficient use of both labour and associated operating assets. The gains we have seen in Japan have been in spite of rather than because of the failure to reform and hinders Japan's long-term prosperity. Japan's creditor status has grown but Japanese relative incomes have continued to slide. Cheers, Dean

Interesting perspective, as always. That said, regarding 2) Fast Retailing (Uniqlo) is hardly representative of Japan, Inc's position on increasing base pay this year. While it's good to have a company like this that leads from the front, most businesses are not planning any increase or, if they are, only a very small, incremental increase at a rate lower than inflation. Also, about 3), there seems to be an ever widening gap between wealth distribution in urban and rural areas, despite the ongoing reliance on pork barrel projects in the countryside. Any reaction?