By popular request, here some thoughts on “Trump risks” for the Japan outlook. My focus is deliberately not on assessing implied risks and implication from possible changes to the U.S. economy. Too much of that already in your inbox…. Instead, I focus on the almost certain boost to China’s export competitiveness in general, the inevitable intensification of Made-in-China versus Made-in-Japan competition in non-U.S. markets in particular. Against these external risks, Japan’s domestic corporate metabolism is now very strong. Unlike Europe, Japan’s elite is united and has the political wherewithal (and societal backbone…) to turn the end of the U.S. sponsored ‘free ride’ into positive energy & opportunity. Enjoy.

Japan’s MAGA worries

At the start of 2025, Japan is the closest it has been in over 30-years to entering a self-sustaining multi-year domestic economic up-cycle. At the same time, the ambitious and aggressive America-first-and-foremost agenda of President Trump will force (unintended….) consequences. MAGAnomics has the potential to disrupt Japan’s path to prosperity.

Two specific “Team Trump” policy goals stand out:

First, raising the costs for Chinese producers to access the U.S. market is poised to force de-facto dumping of Made-in-China excess capacity into global markets, thus eroding Japan’s global competitiveness in general, corporate profits in particular.

Second, if President Trump can deliver his stated goal of a significant devaluation of the U.S. dollar, Japan’s balance of payments and, more importantly, corporate profits will be pulled down hard: every Y10 of Yen appreciation against the dollar basically cuts listed companies profits by approximately 8%. Specifically for 2025, a slip below Y145/$ marks the likely start of a Japan earnings down cycle.

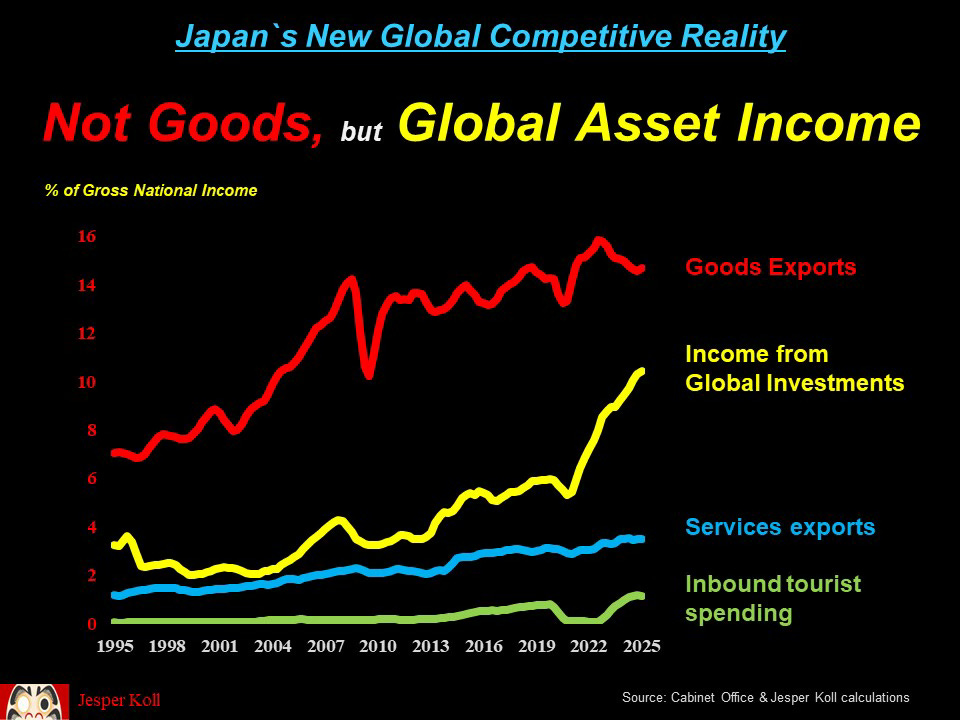

Same old current account surplus…

To understand my concern, let’s take a closer look at Japan’s balance of payments. This offers the best and most comprehensive insights into the evolution of Japan’s global competitive position. And yes, Japan is running a very comfortable - and record high - current account surplus. As President Trump may phrase it, Japan earns more from the world than she pays to the world...(1)

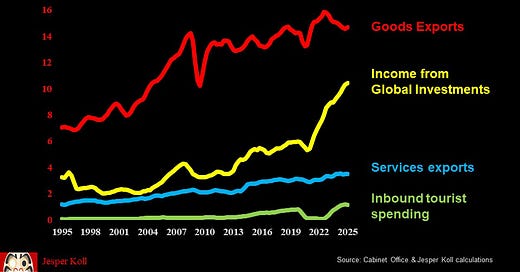

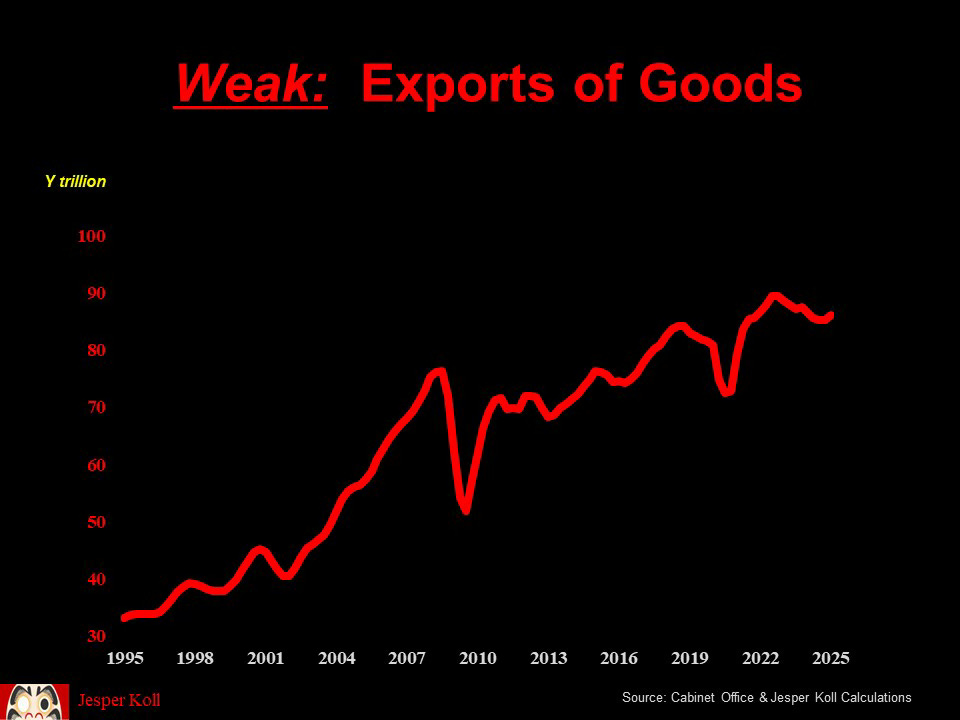

…but radically different growth drivers

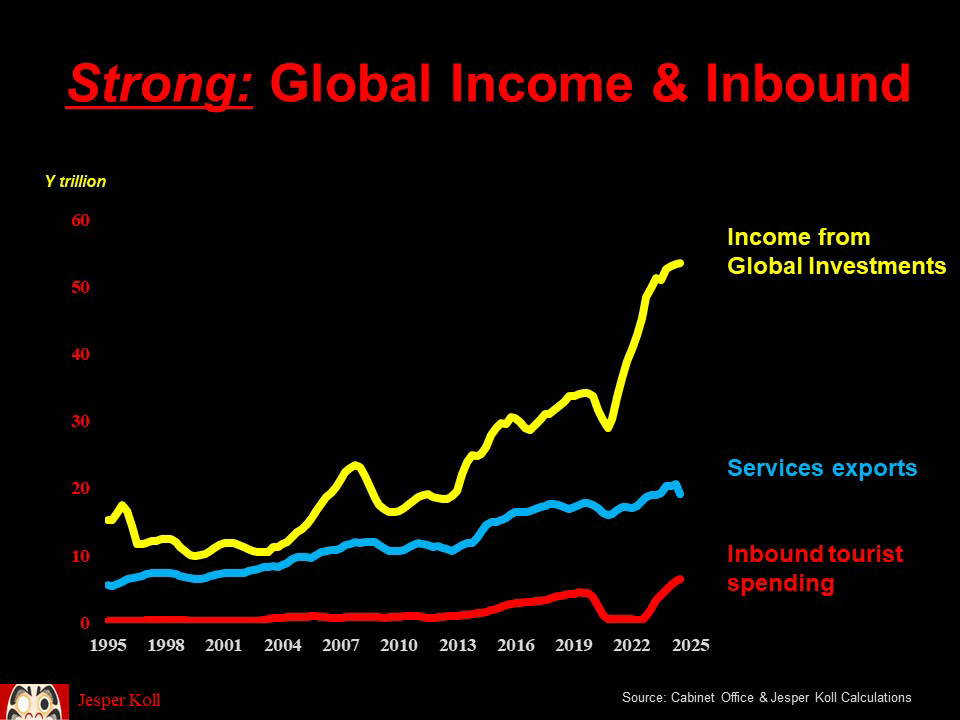

Now let’s look at the asset side of the current account — the goods & services the world buys from Japan plus the income the world pays to Japan for owned-by-Japan global investments. A fundamental new reality has emerged: exports of goods have basically been stagnant, but income earned from global assets has shot-up from less than 5% to 10% of national income over the past four years. Without the surge in overseas investment income earned, Japan’s national income would basically still be below pre-COVID levels.

Make no mistake: Japan has become a ‘trust fund babe’ or rentier economy (living off the assets accumulated by the previous generation…). Japan is no longer an export powerhouse.

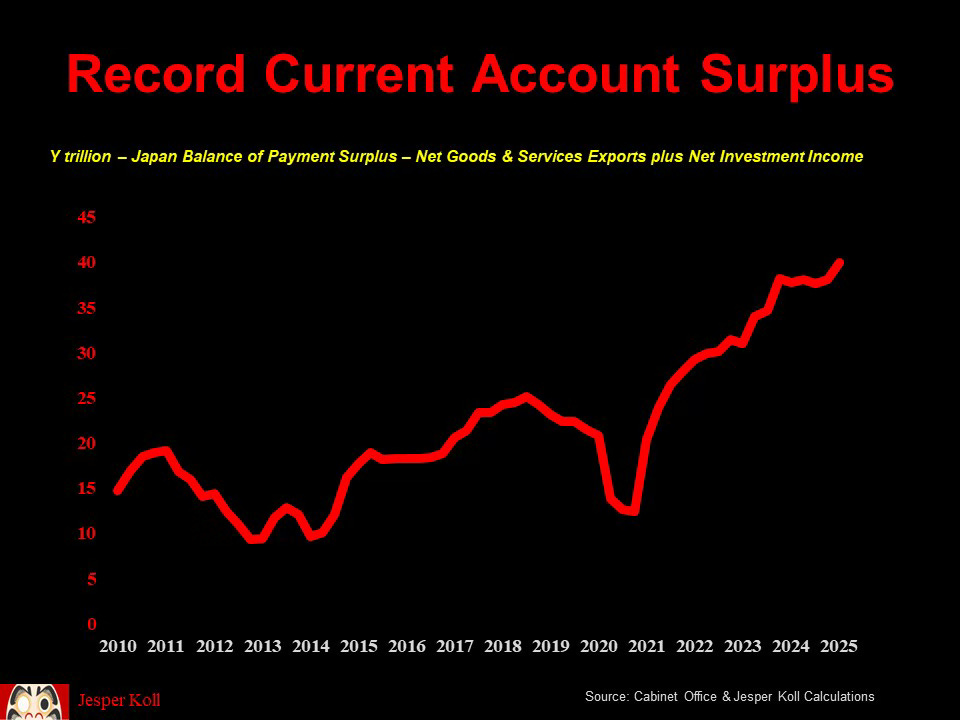

Why are good exports so weak?

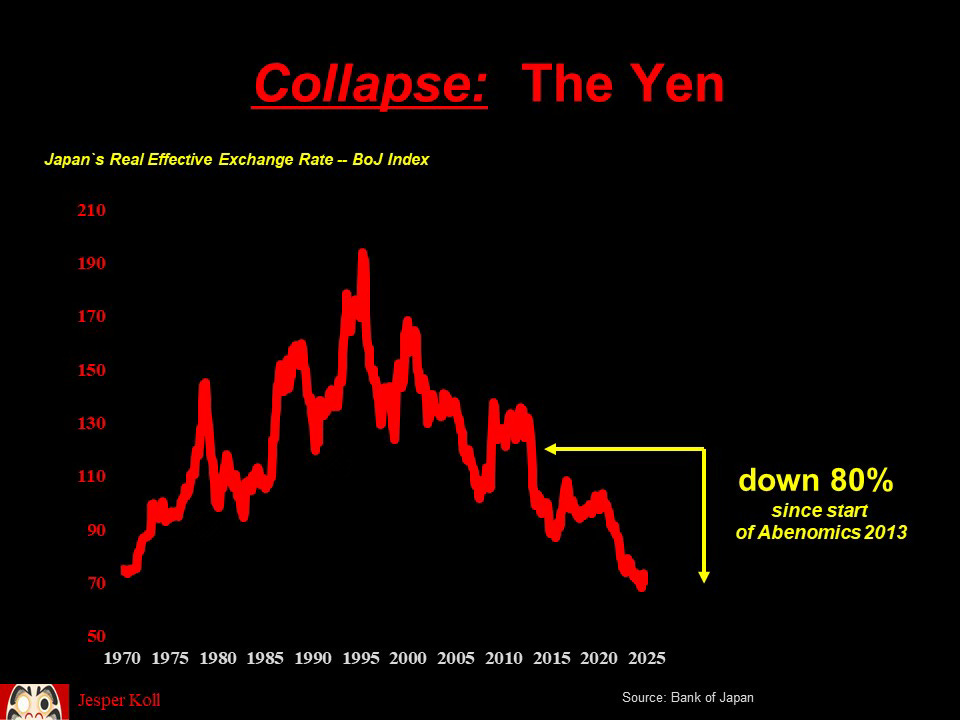

The de-facto stagnation of Japan’s goods exports over the past decade deserves greater attention. It is seriously shocking since it comes in spite of an unprecedented, persistent and deep depreciation of the currency: the Yen has collapsed by 80% since the start of Abenomics in 2013 and is now weaker than it was in the late 1960s, ie. before Breton Woods (according to Bank of Japan calculations of that the real effective Yen). Japan’s exports should be booming…but are not. Or put in another way, the Yen is still not weak enough to boost Japan’s exports. This is because both Japan and the world has changed dramatically.

Made-in-China competition is real

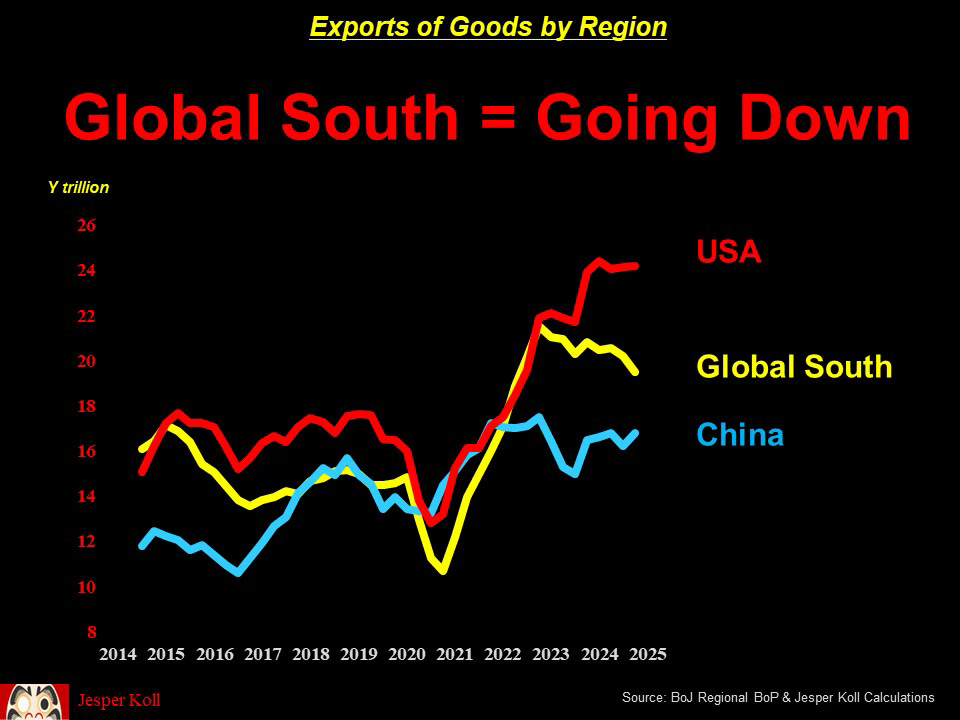

A look at goods exports by region uncovers what’s going on. Japanese exports have remained competitive and well geared into U.S. domestic demand; and yes, the combination of China’s slowing domestic demand and reduced Japanese foreign direct investment into the Peoples Republic (made by Japan off-shore factories typically are equipped with made-in-Japan machinery) have forced stagnation of exports to China (the same is basically true for exports to Europe). Nothing concerning or inexplicable going on here.

In contrast, the standout new dynamics - and reason for my MAGAnomics worries - is a significant drop in Japanese exports to the Global South. This is were head-to-head competition against Made-in-China has intensified, were Japan has been loosing ground, and is poised to loose further market share and profitability if Trump’s policies raise further the costs for China to do business in (or with) America.

China’s manufacturing capability and capacity have grown and evolved consistently. China is now a perfectly viable global competitor to Made-in-Japan. Famously, China surpassed Japan as the world’s number one car exporter; and the breadth of head-to-head competition against China is growing rapidly: first, it was textiles and toys; then the Shinkansen bullet train and electronics; last year, cars; and next up — machinery and capital goods: already China’s exports of industrial robots have more than doubled in the last five years while Japan’s are down 12%. A similar story in construction and mining machinery, up almost 3-fold for China, down over 10% for Japan (same five years).

Made-in-China competition will intensify…

Yes, Japan has performed well in the highly politicized and headline grabbing semi-conductor equipment sector. But it is hard to imagine - even for the Japan optimist - that the Japan moat in the specialized and precision machinery sectors can be defended forever: China spends more than 3-times on Research and Development than Japan, US$500 billion versus US$150 billion; and China is reported to have more than 6 million people working full-time in R&D, compared to an estimated 710,000 in Japan.

Make no mistake: true Made-in-Japan global champions - robot maker Fanuc, factory automation giant Keyence, electronic component powerhouse Murata, to name but a few Japan superstars - are feeling the heat from made-in-chinas relentless rise in overall competitive power. It’s no longer just price. The gaps in quality of manufacturing, quality of after-sales servicing, and qualitative innovation are narrowing fast. Japan knows full well that China is an awe inspiring competitor.

…U.S. protectionism will boost China’s global fortunes at Japan’s expense

Of course, the inevitable trends of China’s value-add climb and consequent Japan-to-China substitution have been predictable and understood for a while. The new force now is U.S. protectionism. First and foremost, U.S. protectionism - or the threat of it - will turbo-charge the trend of Japan’s loss of global marketshare and competitiveness in non-US markets.

Why? Because U.S. protectionism will further aggravate China’s excess capacity - China must keep producing to keep employment, but will loose U.S. customers. The net effect will almost certainly force de-facto dumping of Made-in-China consumer- and capital goods onto the world in general, the Global South in particular. (and, to add insult to injury, as the U.S. withdraws further from global organizations, there will be no credible World Trade Organization or other global sheriff' that Japan could appeal to for help in claiming unfair trade practices or anti-dumping investigations…and it seems highly unlikely Team Trump will give special protection to Japan, particularly in third markets).

All said, for Japan, the net impact of U.S. protectionism is deflationary for both corporate profits as well as aggregate demand - more so because of the (unintended…) but likely global impact unleashed by the worsening China’s excess capacity dynamics than the possible direct hit coming from U.S. demand uncertainty.

Weak U.S. dollar = declining Japan profits

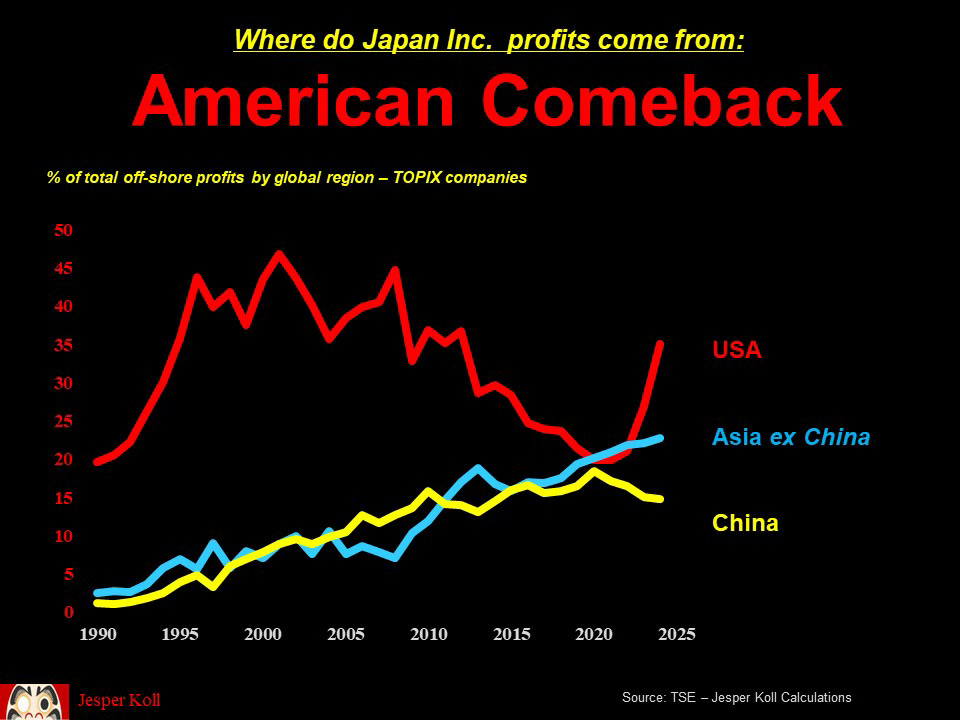

Meanwhile, the impact of a possible weaker dollar on Japan is much more straightforward. The balance of payments dynamics outlined above says it all: the surge in income earned from overseas assets is directly linked to the rise in the US dollar / fall in the Yen, as well as the rise in U.S. interest rates. As much as half of the de-facto doubling corporate earnings over that past decade may be attributed to Yen depreciation (for TOPIX listed companies).

Specifically, for listed companies (TOPIX index) the resurgence of Japan’s corporate dependency on the U.S. has been remarkable: approximately 65% of TOPIX total earnings come from overseas activities — exports or off-shore production or investments; and of these, slightly more than one-third are now generated from the U.S. markets. As you can see from the chart, until five years ago, Japan’s profit dependence on the U.S. had been in relative decline. Now America is back….

All said, the sensitivity of Japanese earnings to the exchange rate is very significant and straightforward to estimate: for every Y10 of Yen appreciation, listed companies earnings are forced down by approximately 8%.

Specifically, what does this mean for 2025? Japanese companies are likely to budget for an average of around Y145-150/$ for the new fiscal year starting April; and with this baseline, profits are expected to rise approximately 8% (current consensus estimate). So against the current Y150-155/$ levels, there appears to be a small comfort zone. Profits should be able to grow as the dollar remains above Y145/$. However, a drop of the dollar below this line would almost certainly force significant revisions down to Japanese corporate earnings.

I’ll leave it for a separate post to think about the —almost certainly negative— implications for the stock market should Japan find itself in a scenario of rising interest rates and falling earrings forecasts.

And now the good news — focus on domestic Japan

Against growing global uncertainty and disruptions forced by the Trump-led “escalate to -hopefully- de-escalate” tactics, let’s end by focusing on the now dominant dynamics in domestic Japan: Yes, a self-sustaining multiyear Japan up-cycle has become a realistic baseline, for both the economy and Yen risk assets (equities, real estate, intellectual property).

To wit: The Bank of Japan recently suggested the deflation gap is now basically closed and — more importantly — made its first revision up to Japan’s potential GDP estimate in almost 20 years, from around 0.7% to around 1%. In doing so, the BoJ endorses the view long held by Japan Optimist that Japan is in both a cyclical and structural up-cycle.

And yes, the BoJ is correct — corporate investment in domestic productive- and human capital has been accelerating consistently for over three years now; and more generally, the pick-up in Japan’s corporate metabolism — record M&A, MBOs, IPOs, spin-offs and buyouts — is poised to deliver a more efficient and productive domestic industrial structure.

The rise in inflation — asset-, product-, wage- and services prices are all going up now — is now ubiquitous across sectors. Above all this confirms Japan is back to being a “normal” economy. After decades of prices pulled lower by excess capacity, excess labor, excess debt and excess cross-shareholdings getting dumped onto markets, now prices are rising because competition for scarce resources and production factors keeps intensifying.

Make no mistake: domestic Japan has got it mojo back; and Trump 2.0 will make the mojo even stronger….

Trump 2.0 — Good for Japan’s Animal Spirits

The immediate effect of Donals Trump’s return to power as the undisputed leader of Japan’s dominant global partner is positive. It will, in my view, be an added catalyst, a turbo-charge oxygen injection to the animal spirits of Japan CEOs. animal spirits and the corporate metabolism. If nothing else, President Trump forces everyone to up-their-game — you can take nothing for granted; if you cannot fend for yourself, you’ll get nothing at best, taken for a ride at worst; and if you do get something, you never know when it will be taken away again. Business as usual it is not. Japan’s corporate metabolism will accelerate further.

Clear-speak: Trump’s America is frightening, yes it needs to scare the world to survive at home; but it thereby empowers global leaders. After decades of “Japan should play a greater part in the U.S.-Japan alliance” Trump’s America puts an end to diplomatic niceties and leaves Japan’s elite with no choice. They now will become more independent, more self-sufficient, more aggressive, assertive, and more focused on self-centered material results. The “free ride” is over — which fuels both the local corporate- and political metabolism.

Importantly, the loss of trust in American generosity may well turn out to be more liberating for Japan’s elite than generally imagined.

Prime Minister Ishiba’s recent kowtowing to President Trump and being praised by the elite technocrats and established media for not upsetting the new hegemon must not distract, in my view, from the growing desire for independence and self-determination the late Prime Minister Abe was able to manifest in Japan.

At the start of the Trump 2.0 Presidency this dynamics has been suppressed in the establishment’s political discourse; but sooner or later the vacuum created by an America Japan cannot really trust will attract new thinking and new leaders who will know how to persuade the public of what is needed to “Make Japan Great Again”. The more MAGAnomics hurts Japan’s corporate and economic performance, the faster the backlash will come. Certainly Japan’s next generation leaders feel and know that waiting for a “Kamikaze” to blow the adversary out of the water is not a good option (by Kamikaze — divine wind — I refer to the original meaning, the huge typhoons that destroyed and dispersed Kublai Khan’s Mongol-Koryo fleet in 1274 and 1281).

Thank you for reading, comments welcome.

From blue-sky but freezing Tokyo -- many cheers ;-j

(1) and yes, a record current account surplus also implies record capital account deficit — Japan earns more income from her production and global assets than she pays to other nations’ for their home-based production or investments in Japan; but Japan also invests more into the rest of the world than the rest of the world invests in Japan — precisely because of this current account surplus. It’s somewhat counterintuitive that a Japan investment overseas should be called a liability for Japan (by common sense it clearly is an asset for the nation); but balance of payments economics counts an overseas investment a liability because it subtracts from the (potential) investments at home. President Trump could have fun with this…

Thanks, Jesper, for this insightful piece and for clarifying your use of the term Kamikaze. Being the son of an Imperial Japanese Navy Special Attack Force pilot who was never given the order to embark on his deadly mission, the distinction is impotant. But I digress; I agree that greater corporate metabolism, i.e more changes of management control, can only be a good thing. It would be important in this context that disposals of non-core or underperforming businesses/subsidiaries by Japanese corporate groups become more prevalent, more so that acquisitions of overseas targets. Japanese management, to date focusing more on buying well, have to become better sellers for the benefits of metabolism to kick in properly.

Thank you Jesper, always thought-provoking!

In December, I wrote a piece which touches on Japan's BoP and some key economic + political implications (There is so much going on!) I thought I would share it here, in case it's of interest.

https://www.eastasiastocks.com/p/japan-vs-big-tech