No bubble, no trouble...

Tokyo home prices are back up at the bubble peak - when will policy makers step-in to stop asset inflation?

Bank of Japan (BoJ) Governor Ueda Kazuo is a lucky man. Unlike his predecessors, who were constantly trying to convince markets and politicians that the central bank was doing all it possibly could to help pull Japan out of a deflationary trap, the new Governor has it easy: the economy is growing, stock markets are surging, and consumer price inflation is everywhere — except in the forward-looking projections of Team Ueda. Prediction: while his predecessors constantly had to revise down the official inflation forecasts, Governor Ueda’s will have to be revised up.

Make no mistake: Governor Ueda knows exactly what he is doing. It has been more than 30-years since inflation was a real problem in Japan, so inflation expectations are still firmly anchored in the deflationary “post bubble” mindset. He is right, in my view, to insist - for now - on the virtues of continuity with his predecessor’s policy. The all-out attack on deflation is still on, 宜しくお願いします….

From cost-push inflation…

From here, the question is what forces will dictate a reversal in the policy elite’s priorities?

In my discussion with leading politicians over the past weeks of what troubles and concerns their constituents are currently complaining about loudest, all point to energy prices as top concern. Importantly, worries about surging energy costs endangering future livelihood come loud and clear from all political stakeholders - individuals, homemakers, business owners, and corporate leaders.

However, when asked what to do about rising energy costs, nobody blames the BoJ, and nobody thinks a change in BoJ policy could help bring down energy costs. For that, according to the politicians, we need more fiscal subsidies and more aggressive price controls, as well as more rapid progress to raise nuclear power generation.

PM Kishida has already passed de-facto subsidy programs for energy and food prices equivalent to just above 1% of GDP over the past nine months; and more is likely to be forthcoming as the voices of constituents’ complaints get louder.

But the key point is this: Japan has a long and proud history of dealing with supply- and terms-of-trade shocks with fiscal support measures. Cost-push-inflation is a job for politicians - not the central bank. (1)

Which gets me to the real break-point in the Japan inflation debate to watch out for: when will the elite declare that residential property prices are in a bubble?

…to the real fear - asset bubble trouble

On December 17, 1989 Mieno Yasushi became the 26th Governor of the Bank of Japan. I had just passed my six-months probation as Chief Japan Economist for the then British merchant bank powerhouse S.G.Warburg and was lucky enough to be invited to one of Governor Mieno’s first speeches.

Here from my notes taken at what would turn out to be one of the decisive historic moments for Japan:

‘It is a great honor to have been appointed 26th Governor of the Bank of Japan and I want to thank everyone for coming today……unfortunately, bad things are happening in our country: graduates from our best universities starting work at our best companies can no longer dream of ever owning an apartment within a two hour commute of their Tokyo headquarters workplace….this is a bubble, this is bad for our country, and I see my primary task as trying by all means to correct this…we must burst the bubble…. (or words to that effect).

To be sure: I was much too naive to realize the full importance of Governor Mieno’s mission. My friends from Salomon Brothers, however, did take the new Governor by his words and became the only ‘research-driven’ investment bank that changed its bullish market forecasts to outright bearish.

Even the Japan-insider and Japan-dominant Nomura persisted in calling for the stock market to rise from the then current 39,000 towards 50,000 or even 60,000 by end-1990 - and so did everyone else except the maverick Americans at Salomon. (1)

Remember Governor Ueda’s insistence that ‘inflation expectation are anchored in the past’? Well, that was very much true then, although obviously in the opposite direction, i.e. inflation forever then, deflation forever now. But unlike for Governor Mieno then, Governor Ueda’s every word and gesture now is analyzed for the slightest hint of a possible change - Japanese markets have learnt the hard way to take central bank speech seriously. Best to err on the side of caution…which, of course, may very well be a sign of how deeply entrenched the ‘deflationary’ or risk adverse mindset of local market players is indeed…

The all-important take-away, however, is this: Japan’s elite does focus on social developments and even today will not tolerate a rise in asset prices if it begins to undermine future generations prospects in general, home affordability in particular.

Yes, real estate inflation does bring benefits through, for example, positive wealth effects. However, the question of home affordability for the next generation will always, at least in Japan, be at the forefront of political and policy concerns. Japan abhors growing ‘gaps’ in affordability and the ruling LDP will always, in my view, try and prevent too strong a gap developing between voters who can afford assets and those who cannot. Here is one area were the LDP and the elite bureaucrats see eye-to-eye.

There are, of course, thousands of analysts focusing on the stock market, but the residential property market is much less scrutinized. Yet it is here, in the property market, that Governor Ueda and Japan’s ruling elite are poised to spot and highlight the first concrete signs of ‘good inflation’ turning to ‘bad inflation’.

So how close are we to a real estate bubble?

Focus on social priorities - real estate prices

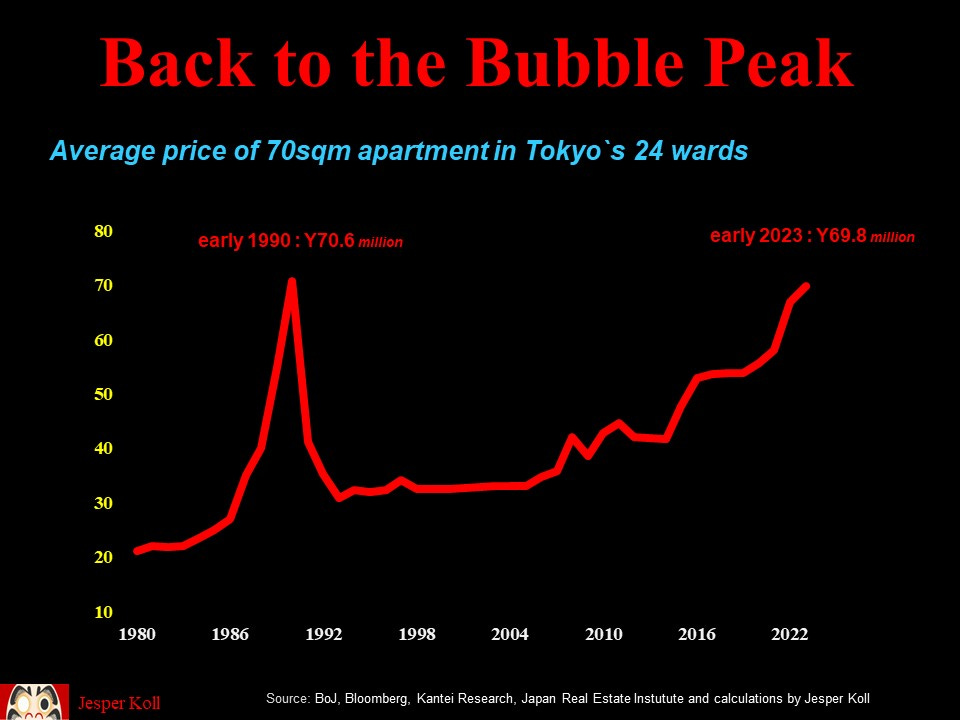

At first sight, we’re there already. Yes, Tokyo residential property prices are back up to the 1990 bubble peak: the price of a 70-square-meter apartment in Tokyo’s 24 wards is now back up to about Y70 million - more or less exactly were it was at the historic peak one generation ago, in 1990.

Remember: In 1980 the price was Y21 million; in 1990 it was Y71 million, and then dropped to Y32 million by 1995…..Governor Mieno’s attack on asset prices was successful…..(70 square meters, or 754 square feet, is the benchmark average size a Tokyo family commands & developers built for then, and still build for today).

What about affordability?

Now, let’s be a bit more granular. What about home affordability?

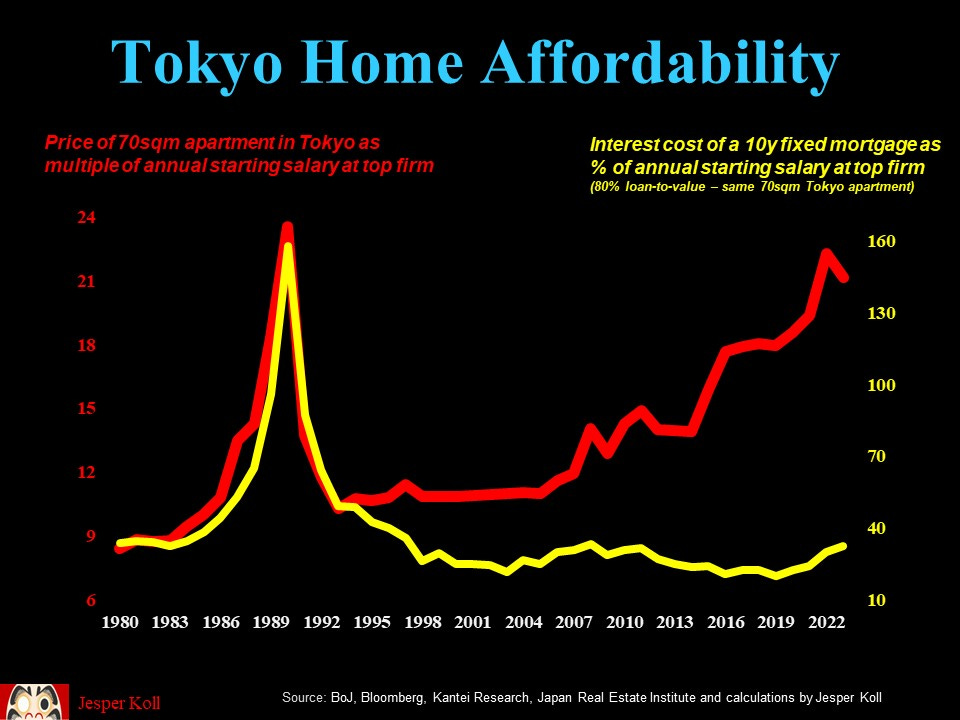

Let’s take Governor Mieno’s affordability metrics as our benchmark - starting salaries for the best & brightest at the top companies: unfortunately, while home prices have risen back to the 1990 bubble peak, starting salaries at Japan’s top companies have — yes !! — stayed stagnant for the past thirty years. So that 70 square meter apartment in Tokyo now costs again about 21-years worth of starting salary income - see the red line in the chart below. (it improved a little this year, as starting salaries for top 50 firms rose on average by approximately 10%, to approximately Y3.3 million).

The good news: low mortgage costs have very much kept-in-check home affordability - despite home price inflation: the full interest expense of a 10-year fixed mortgage for that same 70 square meter home comes to a little less than Y1.1 million, which is approximately 32% of the top-50 firm starting salary (all this assuming 80% loan-to-value, i.e. a 20% downpayment). In contrast, at the peak of the bubble, a similar mortgage cost just above 150% of starting salary - see the yellow line.

Clear speak: home prices in Japan are up smartly, but affordability still remains comfortably high because of the BoJ low interest rate policy. So - for now - positive wealth effects outweigh possible negative societal implications. Japan’s home market is currently nowhere near a bubble.

However, this will change from here. The basic sensitivities are approximately as follows:

a 50 basis point hike in mortgage rates costs the equivalent of about 9% of the current annual starting salary, i.e. would rise from the current 32% of annual salary to 41%

so to compensate for this 50bp hike in mortgage costs, starting salaries would have to rise by approximately 10% - this is possible, but quite a tall order

Obviously these basic sensitivities change for the worse as underlying home prices keep rising.

Moreover, the macro impact of rising mortgage rates is poised to have become more potent because currently almost 80% of all mortgages are floating rate mortgages, quite a significant changes from 10-years ago when the vast majority of mortgages was fixed rate. Surely this potential for a “turbo charged” brake on home affordability demands more study and scrutiny for assessing when Governor Ueda will be ready to break with his predecessor’s policy. Both his words and his actions are poised to have a more powerful effect than what we have been used to from his predecessors. Where Kuroda has to surprise, Ueda may well be able to just tweak.

All said, there clearly is no need to counter run-away asset inflation at present. However, BoJ freedom to act is not just constrained by the Ministry of Finance’s fear of rising interest expense on the massive fiscal deficit, but also by the potential loss of the peoples purchasing power forced by rising mortgage rates.

Most importantly, I am eagerly awaiting Governor Ueda’s first public deliberations on domestic asset prices and the role he ascribes to them for transmitting monetary policy into the real economy. After all, when the all-out-attack on deflation ends, assets prices are poised to be affected the most - even if actions are nowhere near as determined as they were under Governor Mieno’s all-out attack on inflation.

I shall explore the question of when the stock market reaches bubble territory in a future note. For now, I wanted to highlight the importance of home prices in Japan’s political economy - Governor Mieno remains one of the very few global policy makers who openly attacked an asset bubble in the pursuit of social stability and justice to future generations.

The costs of his actions, of course, were very high; but by now it has become increasingly clear that his mistake was not the attack, but on his refusal to accept victory and his stubborn reluctance to mobilize for reflation with just as decisive and aggressive means. Thus he is condemned as the ‘too little, too late’ Governor in the history books. Governor Ueda, I am certain, will not make this mistake and act decisively, on both sides of the deflation-inflation cycle.

Thank you for reading. As always, comments very welcome. Best & many cheers from rainy-season Tokyo ;-j

(1) There is, of course, a fierce and often vainglory-seeking debate amongst economists about the, for some, questionable wisdom of this approach; but Japan Optimist is successful because it tries to get the real-existing Japan right based on experience, practice, mistakes, and observation, rather than by solving for a theoretical optimum in an econometrically elegant model that’s best-ignored-in-the-real-world-for-reasons-obvious-to-anyone-with-skin-in-the-game…

(2) Despite repeated warnings and clear-cut speeches by the new Governor, only Salomon Brothers called for a bear market. In fact, the then head of the office was seen rushing out of the hotel where Mieno had spoken instructing his teams to “short everything Japan - sell both stocks and bonds”. As Mieno’s action followed his warnings - he hiked interest rates aggressively, pushing JGB yields to over 8% and crashing the Nikkei swiftly throughout 1990/91. To this day, this gentleman remains the only-ever CEO of the local Japan operations of a global financial firm who made it all the way to CEO of the entire global firm. There is both money to be made and glory to be had in bear markets…all you have to do it trust in your central banker.

Hi Jesper, thank you for this insightful article. You wisely point out the risk to home affordability that will emerge if mortgage rates rise without a corresponding increase in wages, particularly given the predominance of variable rate mortgages. Do these arguments also point to a potential catch-22 scenario that the BOJ could find itself in if real estate prices continue to rise at current interest rates (absent of wage improvement)? If real estate prices continue to rise that will also negatively impact affordability and increase the pain of eventually raising rates. The BOJ will need to choose between the risk to affordability from unchecked prices vs. higher mortgage rates. I suppose the hope is that, if they find themselves in this scenario, they could thread the needle with a modest increase to rates that has a disproportionate cooling effect while buying more time for wages to rise. Is this the right way to think about the challenge that could arise if real estate prices continue their upward trajectory? Do you see this “doomed if you, doomed if you don’t” risk as a material concern?

Tycho sums it up quite nicely for those of us less endowed in brilliant economic speak. I always read however and attempt to gain insight. Thank you.