The Savings Imperative

Entitlement reform is Japan's real "New Capitalism" - with or without Kishida's leadership

October 12, 2022

At the end of a previous post, Demographic Sweet Spot, I promised to answer why, despite the virtuous up-cycle in both the quantity and quality of employment, Japanese consumer spending has remained stuck in the doldrums. What drives the consistent preference to save rather than spend in Japan?

The short answer is this: the Japanese people know social welfare reform is unavoidable. Contributions will have to go up and entitlements will have to be cut. This is not just about the end of pandemic support, but a structural inevitability. Government promises are gradually being broken, the economics of Japan’s social contract is being re-negotiated one line-item at a time. Both young and old Japanese know they must prepare to pay out of pocket for what used to be free public services. Clear speak: if you don’t save now, your future quality of life is likely to go down.

The bad news — and trust me, as a Japan Optimist it pains me to have to start with this — is that Prime Minister Kishida is about to add to these deeply engrained fears. In coming weeks, he is set to present yet another debt-funded large-scale supplementary budget, possibly as large as 2-3% of GDP.

New Capitalism, or old-style LDP pork-barrel policies?

Obviously some of the new public funds will be put to urgent use as a countercyclical cushion. The loss loss of private sector purchasing power forced by rising energy and food costs commands swift action.

However, the risks are high that the explicit up-shift in entitlements and transfers will further alert consumers to the fact that yes, future cutbacks will not just come, but will now have to be even larger than previously anticipated. Unless Prime Minister Kishida manages to present a genuine investment-led new growth strategy as integral part of this package, Japanese households are poised to dismiss it as yet another old-style LDP package, yet another more-or-less desperate attempt to prop-up falling popularity ratings (1).

Japan deserves a ‘New Capitalism’ growth agenda more than just don’t-know-any-better-business-as-usual handouts. Those in the know tell stories of how Prime Minister Kishida took over ten-thousand pages of notes listening to advisers, counselors and friends over the twelve months he’s now been in office. Everyone agrees he’s a very good listener. We’ll know by the end of this month whether he’s learned how to act; how to invest public resources for future structural returns, rather than just current consumption. I, for one, am ready to be positively surprised…

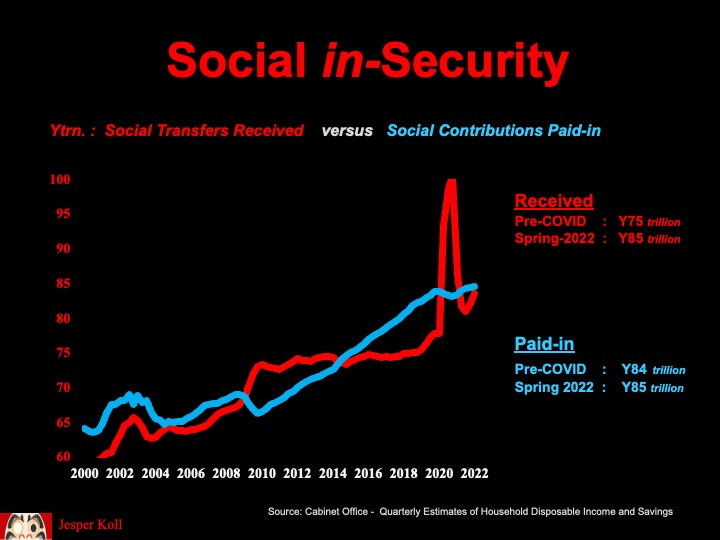

Reality Check: Social in-Security

Be this as it may. Let’s have a look at the facts. Entitlement policies are deviously difficult to track when analyzing the national budget. However, the national income accounts offer insight into the aggregate impact on the national economy in general, the household sector in particular. Clear speak: untangled from budget line-item minutia, here we can actually see whether the people receive more from the government-run social welfare system than they pay-in; or whether the social welfare state takes more than households get (2).

Let me highlight the key dynamics here :

until the Democratic Party took power away from the LDP in 2009, Japanese households in aggregate paid-in more into the social welfare state than they received back: the blue line in the chart was above the red one.

once in power, the Democrats delivered on their election promises and raised entitlements significantly across a relatively wide range of society - education support, child-care support, old-age care entitlement etc. At the same time, they implemented a reduction in social security contributions. Net result: the people received significantly more than than paid-in, i.e. red line went up, the blue one went down; and red is above blue for the first time in the history of Japan’s social welfare state.

as soon as the LDP returns to power with Prime Minister Abe in late-2012, entitlements get basically frozen, while mandatory contributions paid into the system get gradually, but relentlessly pushed up. Within less than three years, Abenomics has turned Japan’s social welfare state from being a deficit (for the government) to being a surplus once again.

the pandemic dramatically disrupted the newfound ‘overfunded’ social welfare state Abenomics had delivered. It triggered an unprecedented jump in transfers to the people, with funds received surging from a pre-COVID steady baseline of Y75 trillion to just over Y100 trillion in 2020, a jump worth approximately 5% of GDP. At the same time, increases in mandatory contributions were basically stopped.

now, by the spring of this year — the last data points available at the time of this writing — total public funds received by the Japanese people from the social welfare state stood at around Y85 trillion, which is approximately Y10 trillion higher than the pre-COVID baseline; and contributions paid-into the social welfare state are basically right where they were before COVID, at around Y85 trillion.

Kishida’s Choice

You can see Kishida’s dilemma. Without a sizable supplementary budget, household receipts from the social welfare state would drop down to the pre-COVID normal, creating a demand deflationary drag on GDP of almost 2%.

Here, it is disappointing that basically none of the debate around ‘New Capitalism’ has attempted to address head-on the urgent need to reform the social welfare sate in general, entitlement policy in particular. One would have thought the cyclical inevitability of the imminent fall-back down back to pre-COVID realities might have moved entitlement reform high up on the must-act-immediately agenda.

Fortunately — if this is the right word — Kishida gets bailed out by the new current crisis. The 2021 energy and food shock demands an urgent countercyclical response. I have no doubt the up-coming supplementary budget will cushion the demand deflationary blow for now; but without reform, the future drawdown is inevitable - which is exactly why Japanese households are poised to save rather than spend.

But what can be done?

Learning from Abenomics

One of the important but overlooked achievements of ‘Abenomics’ has been the decisive reversal of entitlement policies outlined in the bullet points above. More specifically, “Team Abe” pushed through gradual but relentless reform of various programs and delivered significant cuts to promises made by previous administrations.

Result: total social transfers from the government to households stopped rising and got frozen at basically Y75 trillion between 2013 and 2019 (the red line in the first chart). This is a remarkable achievement given Japan’s rapid aging and the thus inevitable up-creep in social security and public healthcare costs (3). Hats-off to the planners and technocrats at the Ministry of Finance.

At the same time, social contributions paid from households to the government were increased from Y69 trillion to Y84 trillion over the same period, 2013 to 2019. Make no mistake: this was a public policy enforced cut in household disposable incomes equivalent to just above 2.5% of GDP over seven years.

Given Japan’s potential growth rate is generally estimated to be around 0.5-0.8%, cutting household disposable incomes by approximately 0.3% of GDP every year by raising social contributions payable is obviously a significant achievement.

How significant? Well, lets me put it this way: Abe’s reform of the contributions citizens must pay to participate in Japan’s social welfare system actually raised more money for the government than the new tax revenues generated by the two hikes in the consumption tax he implemented during his tenure.

However, where the consumption tax hikes inevitably force a dramatic (and thus newsworthy) yet ultimately only temporary distortion in consumption patterns — front-loading ahead of the hike, followed by pay-back once enacted — a gradual but steadfast increase in the social transfer payment burden is much harder to track. Its various components are hidden in the details of not just the national budget but subtle shifts in rules and regulations.

“Team Abe” was never shy and always open about its concerted political will to drive entitlement reform, but it was the tremendous skill of Japan’s elite technocrats that allowed smooth implementation. Abe never really faced voter discontent or a voter rebellion — he won five major landslide elections while he shifted the social transfer balance of benefits away from the people towards the government.

Specifically, this was achieved with gradual but relentless reform where, for example, pension & health care contributions paid by part-time employees were put more or less on par with the higher ones mandated for full-time ones, i.e. cutting the opportunity cost of hiring full-timers over than part-timers ; or — importantly — increases in the out-of-pocket expense for Japan’s socialized health care services targeted specifically at high-income earners. These actions, together with the fact that “Team Abe’s” first budget actually increased the top income tax rate from 45% to 55% gave Abenomics credibility with the people. Here we got tangible and fearless re-distribution policies — tax the rich and make capitalists pay more for hiring part-timers; and that certainly stands in sharp contrast to the sometimes promised, sometimes denied re-distribution ambitions of the still ill-defined “New Capitalism” project.

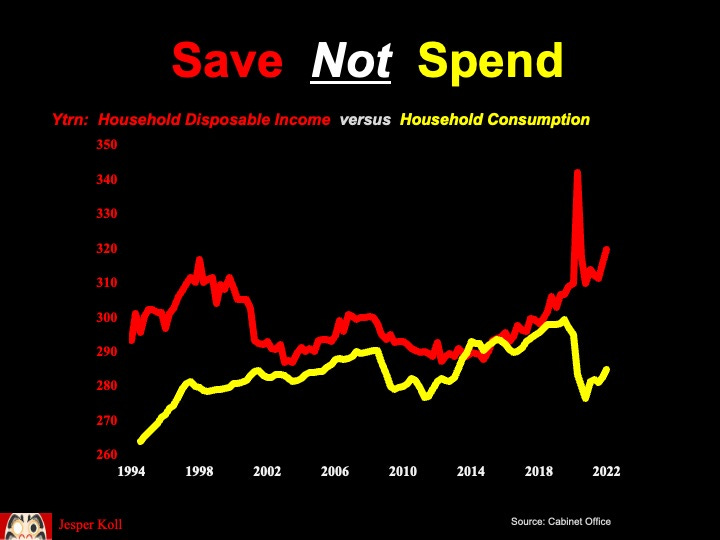

Most importantly, it actually worked: the Abenomics period 2012 to 2019 is the only one where the gap between household disposable incomes and household consumption actually narrowed, i.e. the savings rate actually dropped.

Of course, there may very well have been factors other than the gradual but relentless reform of Japan’s social welfare state that contributed to the growing propensity to spend under Abenomics. But it is interesting that during the social welfare largesse offered by the previous Democrats’ administration, 2009-2012, the propensity to spend actually dropped significantly.

All of this is worthy of further investigation but the immediate empirical evidence is overwhelming: make no mistake - during Abenomics, households actually spent rather than saved, and the unwavering commitment of “Team Abe” to freeze entitlements and raise contributions must have been a significant factor.

Steadfast frugality did not derail the economy because, at least in my view, “Team Abe” also delivered on an unwavering commitment to a relentless pro-growth agenda. Note how, despite the freezing of entitlements, disposable incomes actually rose steadily since 2013/14, pushed higher by corporate leaders actually investing more in human capital, employing more labor.

For now, Prime Minister Kishida has been given some extra time. The urgent need for a countercyclical stimulus allows him to post-pone the real decisions Japan’s structural prosperity depends on - will he steer Japan’s social welfare state back on track to the pre-pandemic austerity dynamics? Or will he command a new course towards more permanent state largesse?

Either way, his ‘New Capitalism’ cannot hide from the issue and must present a credible strategy to counter the inherent in-security in Japan’s social welfare state. More importantly, the longer he post-pones making hard and real decisions, the greater the probability the elite technocrats will have no choice but to make them for him - which is, in my view, exactly what drives down cabinet support rates and pushes up savings.

As always, thank you for reading. Comments very welcome. Best & many cheers from Tokyo ;-j

(1) Support rates for the Kishida cabinet have recently dropped from 45-50% to 35-40%.

(2) The actual workings of the Social Welfare State are extremely complex. It is funded in multiple ways - current contributions, taxes, and investment returns; and it disburses to households via transfers, entitlements, allowances etc — which can come from both the national- and the local government. Fortunately, the quarterly and annual national accounts condense all this into the aggregate receipts and pay-ins for households.

(3) The cyclical pick-up in the economy did help keep government social security spending in check, with the rise in employment reducing “hello work” dole payments; however, the legislated entitlement cutbacks were the most significant force keeping transfers to households’ flatlined until 2019.