Abe Shinzo's quest for a tier-one nation Japan

His overarching goal was to prove America's elite wrong and re-establish Japan's rightful place as a proud tier-one nation

In the late afternoon of July 9, one of the major Japanese newspapers asked for my thoughts on Abe Shinzo, his legacy, and how current Prime Minister Kishida compares. Here an English version of my reply:

When you meet Kishida Fumio for your, say, 3pm appointment, he will tell you what the person he met at 2pm told him. When you met with Abe Shinzo at 3pm, he would tell you what he thought about what his 2pm had said. Abe Shinzo knew what he wanted. He was possessed not just by genuine curiosity, but was razor sharp in his focus on how ideas could help him achieve his primary goal: re-store Japan`s status as a tier-one nation.

I am not being unkind to Prime Minister Kishida. Different times demand different types of leaders; today’s may well be one for contemplation. But Abe Shinzo’s was a time of real existential crisis for his beloved Japan; and also for himself: his first term as Prime Minister (2006-07) had ended miserably. He had come very close to entering history as the man who disgraced the proud and honorable Kishi-Abe political dynasty (1).

The existential threat to Japan was more immediate and urgent. It came from both Japan’s biggest friend and her greatest foe. It reached a climax in 2012: Since the spring, the Peoples Republic of China had become more assertive in challenging Japan’s territorial sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands. More shockingly, in the summer of 2012, the United States foreign- and security policy elite had sent a very stern warning to Japan:

The regular review of the US-Japan Alliance chaired by Joseph Nye & Richard Armitage – both longstanding friends and supporters of Japan -- published in August 2012 opens as follows:

`This report on the US-Japan alliance comes at a time of drift in the relationship. As leaders in both the US and Japan face a myriad of other challenges, the health and welfare of one of the world’s most important alliances is endangered.`

It continues:

`For such an alliance to exist, the US and Japan will need to come at it from the perspective, and as the embodiment of tier-one nations. In our view, tier-one nations have significant economic weight, capable military forces, global vision, and demonstrated leadership on international concerns. Although there are areas where the US can better support the alliance, we have no doubt of the United States`s continuing tier-one status. For Japan, however, there is a decision to be made. Does Japan desire to continue to be a tier-one nation, or is she content to drift into tier-two status?`

The threat was very real – after decades of deflation, economic slip-sliding and growing political regime uncertainty, America`s elite was openly doubting Japan’s viability as a partner and ally. Without America, Japan would be lost.

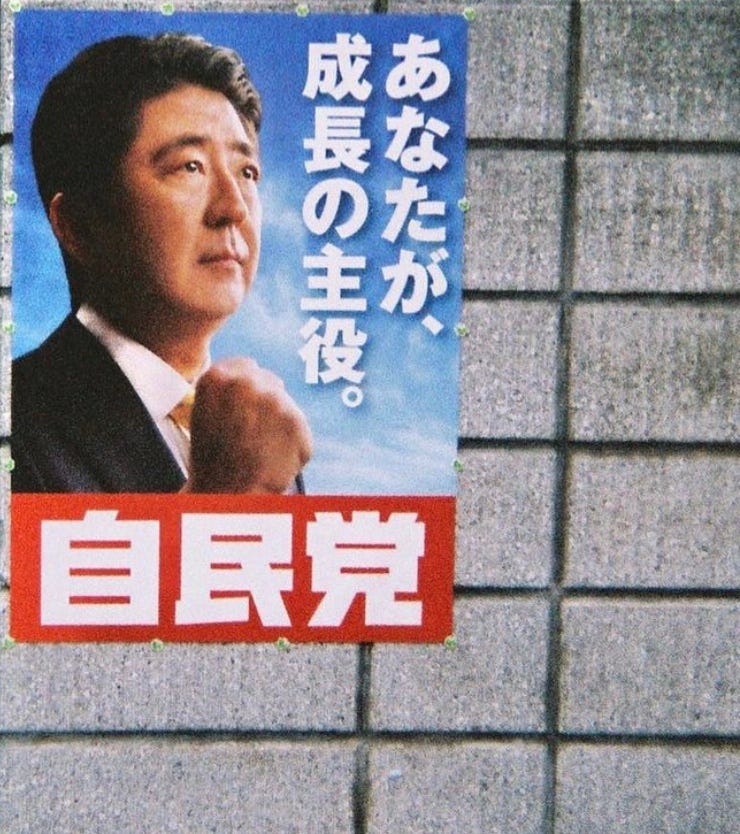

Japan’s elite embraced the stern warning from America, almost happy for the 外圧 gaiatsu foreign pressure from America, finally someone giving a voice to their own frustrations with the dismal state of affairs in Japan. Abe Shinzo seized the moment. To almost everyone’s surprise, he suddenly threw his hat into the ring for the then-in-opposition LDP President election in September 2012.

Importantly, he defied convention by running first and foremost on principle and mission, rather than relying on the typical backroom brokering of trying to pre-arrange support from factions by promising positions: of all the candidates, he was the only one openly declaring that no, Japan will never become a colony of China; and yes, he insisted Japan has got what it takes to be a global contender and top-tier nation. His passion, determination and clear-speak instantly exposed the other candidates as either entitled wannabes or spineless apparatschiks.

Less than three months after winning the party’s top job, the sparks of his passion lit a fire amongst voters. On December 16, 2012 he led the LDP to a landslide victory and return to power. Six days before the end of 2012, Abe Shinzo became Prime Minister, presented his cabinet, and immediately began to work.

His sense of urgency and decision making was unprecedented in Japanese politics. After his unsuccessful first term, he had started to study the history of the world’s great leaders. He had learned that deep existential crisis are huge opportunities; but that there was only one way for him to succeed and pull Japan out of her deep existential crisis: action, not talk; action, not promises; action, not deliberations; and yes, leadership, not consensus – all with an unwavering focus on the goal: re-establish Japan’s rightful place as top-tier nation in the world; not just to prove American fears wrong, but, more importantly, to inspire the hearts, souls and aspirations of the Japanese people.

Abe Shinzo’s actions as Prime Minister speak for themselves:

Strong country, not afraid

He immediately seconded a heavily armed Coast Guard frigate to the Philippines so they could more credibly protect their own South China Sea territory against China`s challenges. The message was clear: Japan is not afraid to project power to help defend a friend and ally. (Interestingly it was Abe`s first Foreign Minister, Kishida Fumio who was sent to the Philippines in early January 2013 to seal the deal, which also resulted in several new patrol ship building orders for Japan…).

Visa deregulation: most successful economic stimulus

He then deregulated and liberalized inbound travelers’ visa regulations for Asian tourists. This did not just demonstrate a new opening of Japan, but it was a deliberate policy to showcase Japanese soft-power and create millions of new grassroots ambassadors. More tangibly, Abe’s visa deregulation quickly turned into one of the most successful economic stimulus policies ever implemented in Japan: within a couple of years, the contribution to Japan’s economy from inbound travelers surged from practically nothing to almost 1% of GDP, with high multiplier effects particularly in regional economies…and all this with practically zero cost.

Tax the rich

Abe Shinzo hiked taxes for the rich. In his first budget, he pushed the top marginal income tax rate from 45% to 55%. He remains to this day, the only advanced economy leader to have done so in the past decade. Again, he did so out of conviction: for Japan to stand united, the more fortunate must pay-up to sustain common social capital because they in turn benefit the most from social stability.

Importantly: no one in Japan’s elite opposed this move. Why not? Because, yes, `Abenomics` did create many tangible new entrepreneurial and business opportunities; but more importantly, Abe Shinzo actually did push through real cuts in entitlements: his model of capitalism was yes, tax the rich, but at the same time cut some fat from the social welfare state:

Entitlement reform

Abe Shinzo also did cut entitlements and reduce the size of Japan`s bloated social welfare state. Incredibly, he succeeded is de-facto freezing total social transfers at basically Y75 trillion between 2012 and 2019, a remarkable achievement given Japan`s rapid ageing and the therefore inevitable up-creep in social security and public healthcare costs.

At the same time, social contributions collected from households actually increased from Y69 trillion to Y84 trillion during his reign. Make no mistake: this is a public policy enforced cut in household disposable income equivalent to just above 2.5% of GDP.

Not a populist

Abe Shinzo was a strongman, but not a populist. To date, the data suggests that Abe`s hike in the top income tax rate resulted in slightly more new revenues for the government (approx. 2.8% of GDP) than his social welfare reform; but be this as it may. In my view, the key lesson for future leaders is the `set menu`: make both the rich and the poor pay more – but in doing so, improve the efficiency of how public funds are being spent by freezing total social transfers paid, i.e. promote better government.

Consumption tax - fair on the young

Of course, he did push through a hike in the consumption tax from 5% to 10% in two installments during his reign. Again, these were not popular policy steps; but they did produce a much better, and arguably fairer, tax system: in a country where almost one-in-three people lives off a pension, taxing at the point of consumption is clearly more fair than taxing incomes, particularly from the perspective of the younger generations…(pension income is tax free in Japan).

Structural reform - from savings to investments

Abe Shinzo goes down in history as the only Prime Minister who actually changed the structural dynamics of Japan’s macro economy. Yes, he actually changed how savings get allocated into investments. He did so by turbo-charging reform of the world’s largest pension fund, Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund, GPIF. Previously run by more-or-less Marxist academics and ultra-conservative technocrats with de-facto no private sector financial professional credentials, Abe Shinzo appointed and empowered a new CIO, Chief Investment Officer, the then London-based successful financier Mizuno Hiromichi.

Within a couple of months, the GPIF made a radical about-turn in its asset allocation: the massive domestic bond portfolio was cut in half to fund a more-than doubling of allocation to domestic equities (to 25% of total assets) and non-yen securities (to 50% of assets).

Clear-speak: within just a couple of months, the equivalent of approximately 5% of household financial assets changed from ultra conservative to `Risk On`. Anyone who has ever dealt with pension managers knows that this sort of radical re-allocation is practically unheard of anywhere in the world of pensions. Hedge funds, yes, they can change allocations on a dime; but for a national pension fund to do so is very radical indeed…

When your national pension fund changes the way it allocates capital, everything changes. Importantly, the GPIF mad it very clear that it was not going to be a passive investor. The new GPIF was activist, holding its managers to account on two fronts: first, on the capital efficiency and return maximizing one - did portfolios actually perform the way they were advertised? And second, similar best-in-class scrutiny was applied on the ESG and social impact front. GPIF even seed-funded some domestic ETFs towards these goals.

Make no mistake, without the GPIF as lead whip and ruthless enforcer of both the newly created Stewardship Code and the Corporate Governance Code, Japan’s capital markets in general, corporate leadership priorities in particular, would still be romancing the good-old days cross-shareholdings, insider governance, and institutional investors who cared more about being part of the club than generating returns.

Importantly, it was not just about radically going `Risk On` on asset allocation, but about actually reforming the GPIF itself. Abe Shinzo’s philosophy and instructions to the GPIF were very clear: to hold companies to a higher standard of governance, your own governance and decision making process must be absolutely best-in-class. The re-invention of Japan’s public pension from sleepy risk-adverse government bond buying machine to globally admired top-tier sovereign wealth fund -admired for both top performance and best-in-class internal governance- was unthinkable before Abe’s push for reform.

Resistance

Importantly, GPIF reform ultimately got stopped by none other than Japan’s Big Business lobby, the Keidanren. GPIF wanted to start managing inhouse individual stock portfolios, i.e. bring some of the equity assets inhouse rather than just outsourcing to external managers. The Keidanren firmly resisted this, arguing there would be too much potential conflict of interest – a national fund should support all companies of the nation, not directly pick winners or losers; and before long Abe Shinzo was forced to submit to the powers of Big Business over the ideals of hart-nosed capitalism.

However, the progress made has been unprecedented – no one has ever changed the structure and dynamics of Japan`s savings-to-investment balance as Abe Shinzo. His empowerment of GPIF reform was, in my view, one of the primary transmission for `Abenomics` to get traction in the real world.

Three arrows — one goal: unity

In the 16th century, there was a Daimyo feudal lord by the name of Mori Motonari. It was Japan’s Sengoku period, a state of almost permanent wars and relentless fighting between Daimyo clans. Lord Mori was known as a brilliant strategist who had managed to expand his territory by playing off his enemies against each other; but he was dismayed because his three eldest sons were more interested in advancing their own selfish goals and did not work together for the benefit of the Mori dynasty.

So one day he calls his three eldest sons and hands each one arrow and ask them to break it. All three snapped the arrow easily. Then Mori Motonagi hands three arrows to each son and again asked to break them. When they were unable to do so, the father looked at his sons and told them: just as you can easily break one arrow, each of you alone can easily be crushed; but if the three of you hold together, you will never be defeated, just as you can never break three arrows.

Every Japanese school teaches this story, and, in a stroke of genius, Abe Shinzo adopted it as the foundation for his `Abenomics`: the three major `arrows` of economic policy making – monetary policy, fiscal policy, and regulatory policy – can all be broken (i.e. are ineffective) when used by independently; but when used together, they cannot be broken and will achieve their goal.

Make no mistake: the core innovation of `Abenomics` was the focus on policy coordination – one team, one dream.

Abe’s prioritization of coordination was sharp reversal of what had gone on in the previous two decades: fiscal policy had been on-again, off-again, torn between the technocrats’ Germanic belief in the imperative of austerity & balanced budgets, and the populist demands of politicians desperate to do something for their base.

Monetary policy was even more confused, with a newly independent central bank insisting on its de-facto impotence: at one point in, the BoJ Governor had the nerve to tell parliament `we`re doing everything we can, but trust me it will not work’ (2).

And finally, regulatory policy was, with the notable exception of the Koizumi era’s consistent attempts to instill a sense of supply-side economics onto Japan, dominated so much by regulatory uncertainty that corporate leaders were left with no choice but to focus on overseas markets for growth investments rather than committing capital to Japan (3).

One Team, One Dream – Abe’s Meritocracy

The focus on `One Team, One Dream` is well documented, with the appointment of ex-Ministry of Finance (MoF) strongman Kuroda Haruhiko to Governor of the Bank of Japan (BoJ) rightly at the center of attention. However, just as important as the close nexus between treasury and central bank was Abe Shinzo’s reform of how top bureaucrats get appointed. In a sharp break with tradition, Abe re-directed ratification and final decisions of top-grade career bureaucrat positions -bureau chief and above – to the Prime Minister’s offices. This power-move was designed to reduce the power of the Ministries pursuing their own institutional interests over the interests of the democratically elected Prime Minister and his team.

Again, the record speaks for itself: almost one-in-four of the annual senior bureaucrats’ appointment proposals – which are proposed by the Ministries – was rejected. This in itself was already unprecedented in the proud history of Japan’s elite technocracy, but Abe Shinzo took it one step further: in at least six cases, Abe’s cabinet appointed someone `junior` to a senior position, i.e. forcing the Ministries to promote on merit rather than seniority. This was nothing short of revolutionary in Japan.

Enemies in high places

Importantly, it was Abe`s Chief Cabinet Spokesman and chosen successor, Suga Yoshihide, who led the charge of keeping the technocrats in line and making sure the senor bureaucrats were part of `Team Abe`. Not surprisingly, both Abe but more so Suga, made a significant amount of high-powered enemies in this, enemies who, in my personal view, did not just contribute to Suga`s relatively swift end, but more importantly, sent a very clear message to Kishida Fumio: if this year`s senior bureaucrat rotations are anything to go by, Japan`s current Prime Minister appears to have given back full control to the Ministries….

Friends in high places

In 2019, within barely one minute after Donald Trump was declared winner in Florida and thus the new President-elect, Prime Minister Abe rolled up his sleeves and demands from his team to find a way to meet the President-to-be as soon as possible. They found a way and on December 17 2019, Abe Shinzo became the first foreign leader to meet the incoming President.

Why the urgency? It goes back to the existential crisis both Abe and Japan faced in 2012 – the fear of America abandoning Japan. Donald Trump had been on record either demanding Japan to pay more for US bases or even face reduced military presence or protection. Abe Shinzo needed to know what the new US leader was up to, wanted to impress him that yes, Japan was back at her rightful place as a top tier nation and reliable partner to America’s ambitions. Again, Abe did not act on impulse but in the cool calculation that early pro-active engagement was poised to pay dividends and allow further progress towards his ultimate goal, an unbreakable Japan-US alliance and partnership.

Most consequential Leader

After the tragedy of his brutal assassination, the US has honored Abe Shinzo like no other global leader before. He certainly earned his place in history, pulling Japan back from the brink of irrelevance towards a newfound relevance as an ambitious tier-one nation. By the end of Abe’s record breaking term, America could not dream of a better, more reliable partner and ally in Asia.

Meanwhile, here in Japan, the legacy of Abe Shinzo is more complex. He was, after all, a strongman, a principled and tough leader who was not afraid to make unpopular decisions. In many ways, he behaved like an American, in the sense that he believed he could create a better future, could inspire his fellow countrymen and women to follow his vision. And yes, the fact that he actually did do more than just talk; actually delivered more than just promise; actually decided rather than just post-pone to another meeting or defer to his advisers – Abe Shinzo will always be admired for the sincerity of his convictions and corresponding actions.

Inevitably, this sincerity and relentless push for action did create frictions. Constitutional reform and preparing Japan to play a larger role in defending the values of democracy, capitalism, the rule of law, and `Western ideals` made perfect sense to Abe Shinzo; but to many here this leaves unanswered what Japan actually should stand for.

In the sphere of economic policy, for example, the notion of a `new capitalism` is a more attractive and worthwhile goal for many than the relentless pursuit of `growth for growth’s sake` at the core of `Abenomics` (or, for that matter, America’s primary modus operandi). As elsewhere, the notion of something vague but somehow better is easier to cheer for than concrete action, urgent goalsetting and KPI accountability (key-performance-indicators and evidence-based policy making was a big priority for “Team Abe”).

Abe Shinzo was open to new ideas; but once he embraced an idea and made it part of his strategy he demanded full commitment, full accountability, and anyone who did not play for the team quickly suffered the consequences.

He was never afraid to exercise power and for him there was no question that the role of the individual citizen must be to protect and serve the state and nation. He tightened media censorship governance with, for example, unprecedented consequences for the editor in chief of a major newspaper or the leadership of the national broadcaster. Education policy and history textbooks become subject to greater scrutiny and focus.

Nobody ever doubted the sincerity of his actions; but many Japanese citizens still today question the necessity of what they perceive to be a fundamentally unwelcome re-definition of the boundaries between individual freedom and the powers of the state.

Remember: in its founding days the LDP called itself conservative precisely because it was the party that vowed to defend and conserve the new constitution against the onslaught of the communists (who wanted to do away with individual rights, property rights etc.). The biggest domestic discontent against constitutional reform is not necessarily against the potential turn towards forward projection of force, but the potential inward restrictions on individual rights and freedoms.

I started out by stating that Abe Shinzo`s was a time of deep existential crisis; and he very much surprised by not just seizing the moment, but by leading the world’s third largest national economy back to global relevance. At home in Japan, in my personal view, he did actually succeed in inspiring Japanese citizens and showing them that they have the power to create a more prosperous future.

Moreover, the fact that he was never afraid to touch deeply engrained yet culturally controversial and unpopular subjects – from female empowerment to constitutional reform to press censorship, to name just a few – did help re-energize Japan’s public debate and democracy.

His legacy of successfully re-inventing Japan as a tier-one nation is assured; how his successors will further strengthen this position remains to be seen – different times demand different leaders.

Thank you for reading ; as always, comments welcome. Many cheers ;-j

PS: I first met Abe Shinzo in the spring of 1988 when I was working as an aide to a Member of Parliament and Abe worked for his father, Abe Shintaro. I was overjoyed when `Team Abe` invited me to be part of his `Buy my Abenomics` campaign. We last met four weeks before his brutal assassination.

(1) Abe' Shinzo’s maternal grandfather was Kishi Nobusuke who had served as Vice Minister for Munitions in the war cabinet of Prime Minister Tojo Hideki, was a founder of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in 1955, and served as Prime Minister from 1957-1960. Abe’s father was Abe Shintaro who served as a Member of Parliament from 1958 to 1991, appointed to MITI Minister and Foreign Minister; he was the leader of Abe faction in the LDP, the Seiwa Seisaku Kenkyukai.

(2) Governor Hayami, who was convinced that creating inflation for inflations sake would lead to a disastrous economic future for Japan and, in my view, deserves to be admired for standing his ground not just against Japanese politicians, but against Paul Krugman and other leading economists who had plenty of `its so easy to create inflation` advise to Japan in the 1990s (before they were forced to learn the hard way that its easy to get out of a debt deflation spiral and liquidity trap on the white paper of an economic textbook, but close to impossible in the real world, i.e. after the Global Financial Crisis).

(3) Of course the strong Yen and the increasingly obvious better growth opportunities in Asian and China markets must count as the dominant factors that drove the off-shoring and `hollowing out` during the 1990s and early 2000s (off-shore capacity as a % of Japan total global production capacity rose from just below 20% to just almost 40% between 1995-2005). However, the increasingly unpredictable domestic regulatory environment contributed significantly. This, at least, is a consistent conclusion from my discussions with CEO and executives over the years.

Here a couple of comments I received via private mail that stuck me :

+ From a longtime professional Japan observer:

"The part I most agree with: the biggest domestic discontent against constitutional reform is not necessarily against the potential turn towards forward projection of force, but the potential inward restrictions on individual rights and freedoms."

--> yes, I am convinced that while the article 9 revision debate is obviously important for global affairs, it all too often distracts from some of the debates around the primary domestic paragraphs and nuances floated.

+ from a well known senior global economic commentator :

"This is very interesting. But Japan cannot be a tier-one nation. There are only two that can be. Japan can be at the top of the second tier."

--> probably the right way to frame global power realities; but America demands from her allies to be ambitious and aspirational, and that is what Japan was in danger of losing.

+ from a Japanese Member of Parliament :

"You're always too optimistic on Japan, but this time you're right to point the high degree of coordination and administrative competence of Abe Shinzo's cabinets; but you have to admit that the first half of Abe's reign was much more powerful than the second half."

--> The forced resignation of Amari Akira end-January 2016 marked, in my personal view, the inflection in Abe Shinzo's policy initiative momentum. Loosing a key dealmaker and admired expert policymaker who could get even the most stubborn technocrat back in-line with "Team Abe" was the beginning of Kasumigaseki's elite clawing back power over the Kantei PM offices. The fact that the political fund problems for Amari started shortly after Abe decided to post-pone the VAT hike is one of the more interesting great coincidences and mysteries in Japanese power politics.

+ from a Japanese university president :

"You are right on Abe, but wrong on Kishida".

--> as I wrote, different times demand different leaders. Abe knew what he wanted, and had the team to get things done at unprecedented speed. Clearly, Kishida is very different; whether today's Japan can afford the luxury of more contemplative, less decisive, less reform-minded leadership remains to be seen. The first real test will come in November/December when Kishida will have to present his first real budget - lofty promises of 'new capitalism' get stale quickly if not followed by concrete fiscal incentives and re-direction of budget allocations. Let's hope that we'll get more significant and ambitious reforms across both revenues and expenditures, rather than just beefed-up defense spending.

Thank you for sharing this detailed analysis. By the way, what has happened to Taro Kono?