Cracks in the consensus

Japanese politics is approaching a breaking point - the people are angry at inflation & immigration; and the LDP is being disrupted by MAGA and the new US leadership style

On July 20, the Japanese people will select 125 Members to the Upper House of Parliament. Although the vote is for only half of the 248 seats of the technically less important Upper House, this election marks a potential breaking point in Japanese politics: it is the first nationwide vote since Japan’s economic, social and geo-strategic status-quo have all been turned upside down.

The people are angry - inflation is cutting their purchasing power; immigration is challenging proud social norms; and the post-war national consensus trust in America as Japan’s benefactor, guardian, special partner and ultimate role model is quickly turning from disbelief-at-what-is-happening to mistrust and discontent.

Make no mistake - this is about so much more than the tariffs: the ruling LDP’s foundational raison d’être was to be America’s independent but loyal agent in liberated-by-America-now-democratic Japan; and this core is exactly what is is being disrupted — the emerging realities of America’s new national priorities, economic agenda and undemocratic leadership style are, simply put, unacceptable to the Japanese people, thus undermining LDP credibility.

Importantly, the above 60-years old generation are disproportionately affected by all three forces; and typically they account for almost two-thirds of all the people who actually go out and vote (voter participation is usually just a touch above 50%, but highly skewed to the elderly - unless the new SanSeiTo slogan “Politics is Rock’nRoll” brings out the youth vote this time, see below).

Of course much of the seat-by-seat outcome of this election will still be decided in the trench warfare election district-by-district fights: for the 125 seats, there are 522 candidates from over 15 parties — and one must never underestimate the ability of the LDP-Komeito ruling alliance to divide-and-rule. However, the LDP and Komeito machine is getting old; and focusing on numbers-only analysis risks missing the structural groundswell dynamics beginning to buildup in Japan’s socio-political dynamics:

Japan’s long established post-war narratives and national consensus is beginning to crack; her established political franchises are structurally too ossified to adapt to the new realities; thus opening a path for new and more extremist political leaders to emerge — Japan’s national narrative will begin to change, mirroring to some extend the nationalist-populist Zeitgeist dominating elsewhere.

No, there is de-facto zero risk of political extremism or a national populist agenda coming to Japan in the immediate future. This is because, unlike America and Europe, Japan’s elite bureaucracy is still both trusted and powerful. They are the effective stewards of the national agenda; and after the elections, they will become even more powerful: when elected politicians are struggling to maintain a majority in parliament (and fight for positions as new leaders inside their parties…) policy making defaults back to the bureaucracy. However, sooner or later the political vacuum will attract a charismatic leader promising to make Japan Japan again…

Now let’s be practical and focus on the coming political dynamics and implications for economic & financial policy. Two major forces will dominate:

1) the LDP-Komeito ruling coalition of Prime Minister Ishiba is poised to loose even more control of parliament and become even more pre-occupied with endless coalition and alliance building negotiations and policy horse-trading.

PM Ishiba was already forced to run a minority government in the lower house after last year’s lower house election loss. Now a de-facto minority government in both houses is at best more inefficient, at worst more unpredictable and unstable.

Importantly, even if the LDP-Komeito coalition looses the majority in the Upper House, there is no legal or rule requirement for the Prime Minister to resign.

A parliamentary vote on the head of the government must be held only after a Lower House election. Or after the entire cabinet resigns. It is highly unlikely that the current cabinet would do so - not only do they like their prestigious jobs, but they also would not resign unless the LDP has somehow secured a majority vote in the Lower House to ensure the Prime Minister and a new cabinet leader comes from its ranks.

There is precedent of a Prime Minister staying in power after loosing the Upper House: Prime Minister Naoto Kan stayed on after his Democratic Party of Japan lost control of the Upper House in 2010. Kan stayed in power for one whole year after the election loss (he resigned in September 2011 to take the blame for mishandling the Fukushima disaster). However, his coalition at the time controlled the Lower House with a supermajority — in sharp contrast to the minority government of Prime Minister Ishiba. If you like politics, Japan’s political kabuki will get exciting…

Importantly, PM Ishiba is actually in a relatively strong position, albeit perhaps for all the wrong reasons: if he does the honorable thing and offers to resign to accept the blame for the election loss, the LDP would be forced to elect a new leader, who’s first job must be to secure enough votes from lower house members to help him/her become Prime Minister.

In other words, the next LDP President will have to be elected with a primary focus on whether he/she is acceptable to the LDP’s current (or future) coalition partners — without this triangulation they won’t get the parliamentary majority required to vote him/her into office. Why bother?

This complication, by the way, is one of the key reasons for why no-one in the LDP is ready to challenge PM Ishiba. Make no mistake - in the here and now, there is a lot of downside to wanting to become the next LDP leader, compared to very little upside…

And yes, PM Ishiba dissolving the lower house and forcing a general election would, for all intends and purposes, be tantamount to political suicide by the LDP. Why call an election when you’ve just lost an election?

Against this, there is an outside chance that the opposition parties feel empowered by the upper house results, gang-up against the LDP, force a no-confidence vote in the lower house, and thus an election. How long can the LDP continue to win at the “divide-and-rule” game in parliament?

Clear speak: party politics & jockeying for positions will dominate, while led-by-politicians policy making will take even more of a backseat. For the foreseeable future, Japanese politics will be all about whom you know and whom you can trust to cover your back; not what you know and what you think should be done….

How long will this political stalemate last? Until the next lower house election. Technically this must be held no later than October 2028.

More practically speaking, from the LDP’s perspective, the next election will be called when a genuine challenger to PM Ishiba emerges from within the party.

This someone will have to

1) have lined-up enough funding to actually fight a lower election; given the still in-limbo legislation on how money-and-politics ought to be governed, raising funds at scale is a bigger problem than it was in the past…

and 2) be charismatic enough to not just capture the imagination of the people but who can convince voters that the only way forward for Japan is by handing power back to the trusted hands of the LDP.

Personally, I think it unlikely this will happen in the foreseeable future. Let me be clear: there are plenty of ambitious younger LDP members who want the job; but anyone with Machiavellian instincts will want to let lackluster Ishiba muddle through for a while longer, ideally until there is a more acute “crisis” that demands a strong man (or woman) new leader. No crisis, no opportunity.

Who? At this stage, my money is on either Kato Katsunobu, the current Finance Minister and darling of the bureaucracy; or Takaichi Sanae, the woman favored by PM Abe to lead his legacy. Hayashi Yoshimasa, the current Chief Cabinet Secretary, is also in the running. Note: the next LDP President elections are not until September 2027….and right now, nobody has found a way to raise money to actually stage a viable challenge.

Which gets us to the important second major dynamics:

2) the elite bureaucracy will become even more empowered to run the nation.

Good thing: they actually do know what they are doing and bring not just of best-in-class technical competence, but also highest integrity to the national interest. Importantly, they are both trusted and feared by the business and finance elite. Without consistent majority-backed orders from elected leaders to do otherwise, the technocrats are poised to keep Japan a relative bastion of stability against populism, nationalist exuberance or nostalgia. Boring, perhaps….but highly competent, certainly.

As an aside, and in sharp contrast to the new US dynamics, Japan’s elite technocrats are very committed to consulting with private sector innovators, plutocrats, techBros and financial pirates; but they are also committed to keeping them as far away from dictating the policy agenda as possible. This is not a contradiction - Government is to serve the public, not private interests. (here let me be clear: I am the first to admit that Japan’s elite bureaucracy are the world champions of defending incumbents and established vested interests — they are the ultimate guardians of the status quo. Creating new entry and new winners is not in their nature and close to impossible without political leadership; but, in Japan’s case, they are also phenomenal drivers of “kaizen”, incrementally improving the status quo — moving slow and perfecting things, not moving fast and breaking things).

More specifically, a stronger elite technocracy implies Japan will stay on track for both fiscal consolidation and monetary policy normalization.

I have no doubt that political calls for greater fiscal stimulus and public support measure will get louder. Politicians will default to finding cheap ways to buy public attention and favors; but the risks of these policies actually becoming law are slim, precisely because of the coming political and parliamentary fragmentation. Lame duck politicians can be a nuisance, but are no threat to the elite technocracy’s focus on both monetary normalization and fiscal consolidation.

Importantly, the shift in power away from politicians towards the bureaucracy is already empirical: during the Abe and Suga administrations, almost one-thirds of the elite Ministries proposed candidates for the annual re-shuffle of senior bureaucrat positions were rejected by the Prime Ministers Office and replaced with candidates sponsored by the Prime Minister’s team. Since then, under both Kishida and Ishiba, the bureaucrats got 100% of whom they proposed. Clear speak: under Abe, the elected executive ran the administration; now the administration runs the elected executive.

Bad thing: the elite bureaucracy can neither create nor implement a genuine pro-active vision for Japan’s future. They’ll keep perfecting the current directives and strategic priorities; they’ll play expert defense against U.S. or Chinese demands for change; drowning opponents by Powerpoint, requesting endless follow-up meetings, and persistently demanding ever more detailed information are but some of their preferred weaponry. But what they absolutely won’t do is invest technocratic capital and personal careers to push for a new strategic vision or proposal with any political leader who’s probability of staying in power for more than one budget cycle is low. And that, for the foreseeable future, will be the most likely operational reality in Japanese policy making.

So Japan will stand out on the global stage - efficient administration, no majority-backed “vision thing”. In a world increasingly dominated by strong leaders with “my way or the highway” leadership styles, this may actually be a good thing for Japan.

Here, I do not worry that Japan’s political paralysis will make Japan less relevant on the global scene. The best Sumo & martial arts fighters win by exploiting their opponents weaknesses and inconsistencies. Patience may well turn into an advanage for Japan, particularly since the real fight is elsewhere, ie. America versus China.

As global ideological battlegrounds harden, Japan’s patient but steadfast demonstration of best-in-class administrative competence and conservative pragmatism could very well result in global trust in Japan rising. Japan become the voice of reason.

For example, it is already clear that Japan’s steadfast prioritization of not just maintaining but strengthening multilateral institutions and frameworks puts Japan in pole position as mediator between rising nationalist and protectionist forces in general, U.S. - China antagonism in particular.

Be this as at may….

Now, let’s focus and dig in to uncover why the Japanese people are angry and upset with their political leaders :

Yes, inflation hurts

Ever since PM Abe appointed Governor Kuroda to the Bank of Japan in 2013, the Prime Ministers Office, the BoJ and the MoF have been committed to an “Accord”: they will closely cooperate and coordinate monetary, fiscal and regulatory policies with one overarching goal: to end deflation and achieve a positive inflation target of 2%. It marked the end of almost three-decades of discord, and this Accord is still in place today.

However: to date, Japanese consumer price inflation has been running for 39 months ABOVE this 2% target. The latest print is 3.7%.

For the Japanese people, this persistent inflation creep has been devastating (particularly since it comes after basically one generation of an extremely stable modest disinflationary equilibrium).

Not speaking as an economist, but as a long-term participant in Japan’s society: there has been an enormous change in social norms over the past twenty years: in almost all aspects of Japanese life, KPI or performance measurement targets have been introduced, with managers incentivized to take action when targets are not achieved. Office workers are penalized when they overshoot their weight targets set in the annual “ningen doc”, the annual medical check up; pregnant women are scolded when they gain too much weight. What signal does it send to the people when the official inflation target is allowed to overshoot for more than three years?

Back to economics: Yes, nominal incomes have been rising steadily, but because of broad-based inflation, the gap between nominal- and real disposable income has widened to new historic highs: the real purchasing power of the Japanese people is stuck at levels last seen in 2018. For pensioners — who make up almost 60% of all voters — real purchasing power may have dropped by as much as 30% over the past three years.

Of course, BoJ Governor Ueda and other policy makers acknowledge the rise in prices, but continue to worry publicly about the “break in Japan’s 30-year deeply entrenched deflationary mindset” not being complete. Personally, I may have some sympathy with this desire to err on the side of caution; but it is clear that the Japanese people are getting angry at the policy makers forcing a transfer of hard earned voters purchasing power to corporate profits and fiscal coffers.

Inflation has always been the democratic battleground where vigilante voters or citizens hold rulers and policy makers accountable. And voters now have little sympathy for experts’ pontificating about inflation expectations or debating the merits of the GDP deflator versus the core-core-ex CPI as the proper academic measure.

What matters for the polls is that, with 39 consecutive months of above the 2% inflation target:

a) Japanese inflation is NOT transient;

b) not just due to the weaker Yen;

c) not just due to rising food prices;

d) possibly due to over-tourism

and, most importantly in my view,

d) can no longer be kept in check by government price control or income support measures.

There have been at least four special policy support measures designed to offer income support for people hurt by rising food and/or energy prices over the past three years, with no tangible results (obviously so because income support measure are always temporary and only work if inflation is indeed transient, which clearly is no longer the case in Japan. Just as Japan had stop-go-stop-go demand cycles in the 1990s when extra budgets temporarily boosted demand but the underlying demand kept on weakening, we not have stop-go-stop-go inflation cycles as the temporary support measures run out against the increasingly strong underlying uptrend forced by both rising demand and supply constraints stemming from Japan’s factor endowments).

Opinion polls consistently highlight inflation as the number one concern of the Japanese people. What’s shocking is that, the policy proposals to counter inflation all follow the same pattern: added income support by either cutting the consumption tax for food or in general; and/or cash handouts. Clear speak, although nuances differ everyone wants to fight inflation by boosting demand.

Notably absent: not a single party nor individual politician proposes supply-side reforms - of any kind.

The surge in food prices in general, rice prices in particular is obviously traceable to an outdated and long-standing uneconomical national and local agricultural policy. Prime Minister Abe attempted to reform agricultural land use by deregulating ag-land purchases, hoping to get some consolidation and increases economies of scale and greater mechanization so that food supply capacity and elasticity could be brought into the 21st century. Complete failure, blocked by local interests and general inability of the LDP in particular to promote rationality and logic onto a proud, but outdated agricultural policy ecosystem.

Here, it must be said U.S. President Trump is correct in his instincts: Japan has a shortage of rice, America has a surplus….how can you argue for free trade in cars when you are unwilling to let supply meet demand in rice? And yes, if U.S. rice does not taste good, let consumers decide.

Of course, agricultural policy anywhere in the world, including the US, is riddled with government intervention and politicians harvesting the farm vote; but in the summer of 2025, the LDP in particular stands accused of having made zero progress of steering Japan towards a more efficient and economically rational food supply chain — despite having identified the bad economics of Japan’s ossified policies multiple decades ago.

The people know that food prices are not rising because of a weaker Yen making imports more expensive, but because of the dying-out farms are not being revitalized and modernized. The LDP is poised to pay a political price.

Yes, fiscal consolidation hurts

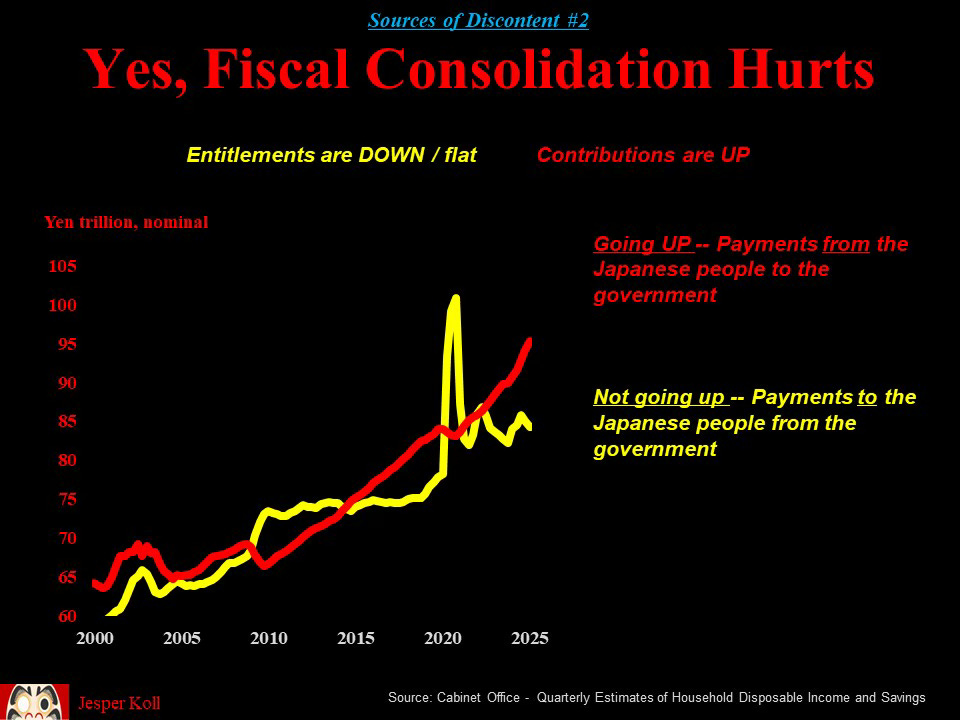

Which gets us to another economic reality that bears pointing out: fiscal consolidation is real and hurts voters. The national income accounts leave no doubt that while contributions from the people to the government are rising steadfast, actual entitlements are falling. In fact, the Japanese people now consistently pay more than Y10 trillion (1.5% of GDP) more into the government (taxes, social security, pension, healthcare) than they receive in total entitlements (pension, healthcare, social security, education) .

This is a part of PM Abe’s reform agenda that did actually get implemented.

The chart confirms that during the period when the LDP had lost power to the DPJ-led opposition from 2009 to 2012, enticements received went up while payments went down. PM Abe reformed this by raising in-payments consistently and, since 2016 in-payments from the people have consistently risen faster than out-payments to the people (with the exception of the pandemic years).

Here is one reason for why Abe was popular with the Ministry of Finance, but unpopular with the LDP populist mainstream….the key point, however, is that Japan’s fiscal consolation through entitlement cuts for the people is already very very real.

More, or less fiscal consolidation ahead?

Importantly, PM Ishiba has promised to set up a new advisory council this autumn, specifically tasked with a holistic review of Japan’s entire entitlement ecosystem.

This council is poised to become a fertile ground for forging policy compromise and new alliances between the LDP and other parties. This is where the technocrats fiscal conservatism will clash with the populist political temptations. It could also become the catalyst to reverse another one of PM Abe’s achievements and legacy…

Note that, in addition to the web of entitlements for individuals aggregated out in the above charts from the national income accounts, Japan has an intricate web of “financial socialism” — government guaranteed loans, preferred interest rate loans, special tax free loans etc. At this point, it is not clear whether the new council will address these as well, but any real reform of the entitlement and public support system would obviously be incomplete without doing so.

More immediately, what matters for the elections is that the Japanese people are seeing their purchasing power cut by both inflation as well as the realities of steadfast increases in non-tax contributions to the government while entitlements are being cut. The fact that the latter is occurring while the population is aging rapidly is actually remarkable - typically public sector entitlement spent is supposed to go up as health-care and pension payouts rise as more people get older. But for the people, less is less….so here is another source of discontent poised to come out at the polls….

What about immigration?

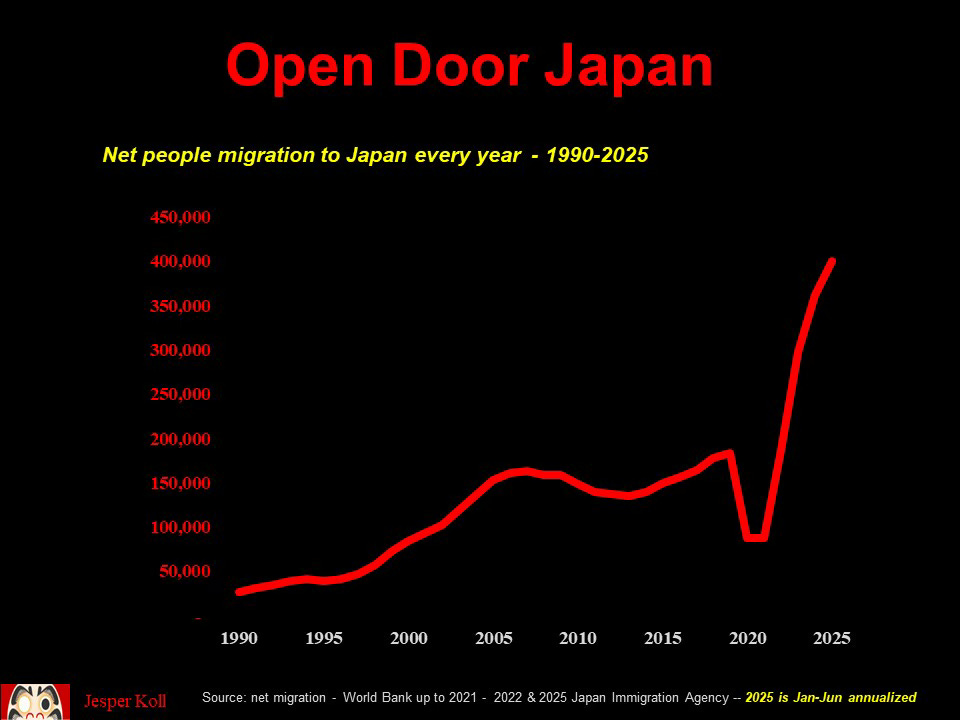

Opinion polls suggest immigration ranks somewhere around the 5th or 6th most important issue for the polls. However, several of the new parties — particularly the SanSei Party — have made immigration and the need for a “Japanese First” policy focus their battlecry (SanSeiTo = Do it Yourself Party….). And they are the party gaining strongly at the margin, with their support rate going from barely 1% last year to almost 5% now.

It is hard to underestimate the radical change that has occurred in Japan’s immigration policies. Doors were definitely more or less closed - when I arrived in the mid 1980s, there were little more half-a-million non Japanese living and working here. By the end of this year, it’s poised to be close to 4 million. The realities “Open door Japan” comes through in the migration data (people receiving working visa).

The SanSeiTo is politically savvy. Their candidates are about 10-years younger than the old established party candidates. They present themselves well to both the younger voters as well as the older ones who are discontent with the establishment in general and, in my view, the inability of the LDP to promote next generation leaders.

Importantly, the SanSeiTo is far from being anything like the AFD in Germany or other nationalist parties that caught the imagination of the people while the established parties are stuck in their ossified ways. Importantly, they are neither pro-China nor anti-American ; but they do make a strong case for “business as usual is not an option anymore” — which actually resonates with anyone working for or running a company here in Japan.

All said, the anger amongst the Japanese people is real. It is fueled first and foremost by inflation, with immigration and loss-of-trust in America as a role model adding to a general sense of discontent. Yes, it’s only an upper house election; but it’s poised to mark the start of more intense political re-shuffling, as well as national soul-sourcing. The elite technocracy will be there real winners and defend against populist economic policies - until a more charismatic political leader emerges.

Thank you for reading — as always, comments welcome. Thank you & many cheers from a boiling hot, but blue-sky sunny Kyoto. ;-j

PS: for the SanSeito, I’ll go into their suggested policies at another time; but here is an English language article written by its dynamic leader, Kamiya Sohei…..and you have to admit their second campaign slogan after the “Japanese first” strikes a refreshing cord: “Politics is Rock’nRoll”. Lets hope this brings out the youth vote…

PS: for a more detailed view on immigration, please see the previous post here Run Ri

Thanks for this interesting and informative piece.

Regarding SanSeito: interesting rebranding, and I can see the appeal of something that shakes up the usual political messaging. But slogans aside, it's the content that matters — and personally, I find their manifesto troubling. Let’s hope the youth vote looks beyond the noise and asks the harder questions.

Ok so there are some epic external challenges out there (Trump, WWIII…) and natural disasters will always hit the headlines BUT

As you say the elephant in the room domestically is the painfully unhelpful legislation around the agri sector in Japan. As an individual with a fulltime office job, I can own farmland and write off any amount of agri-toys that I use on my 1,000m2 “farm”, against my personal tax bill without producing much of anything.

A family office with agri experience on three continents wanting to invest several $10m in specialist farming in Kyushu… cannot.

Agri reform is the domestic battle that Japan MUST win.