Japan reality check #3: what is Japan's economy really bad at?

Japan has no corporate superstars, does not pay its workers, and household wealth is not really growing -- nothing that cannot be fixed

This week, a Japanese bureaucrat sent an email: “Jesper, I need your help. I read your reply to the Davos-bound business leader who wanted to know three good things of Japan’s economy. I agree with your reply and I am happy to learn our business leaders now want to promote Japan. But as you know, us Government officials, we are charged with making Japan better. So I want to know: If you are to mention three bad things about Japan’s economy with data, what would these be?”

A simple and important question, particularly if you’re a Japan optimist. Keeps me honest, right? Here’s my answer:

1) Japan has no corporate superstars

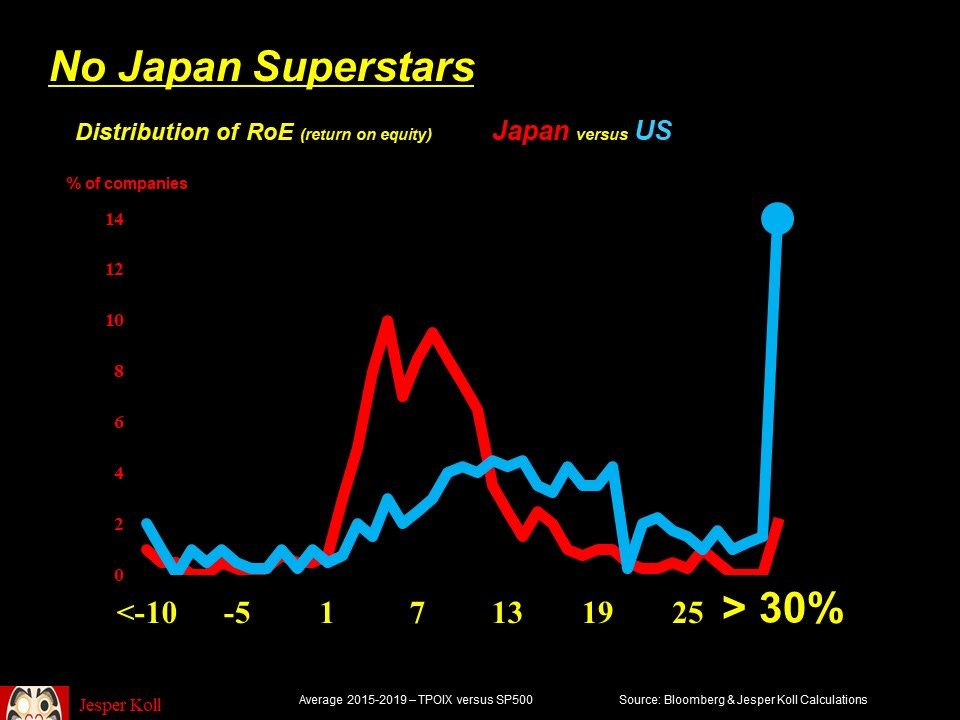

Corporate Japan has done an amazing job of improving capital efficiency. Over the past decade, the return on equity has basically doubled and now stands at the 8% target suggested in the Ito report that kicked-off genuine Corporate Governance reform in 2014/15. However, Japan has no global superstars, no “national champions”.

The distribution of Japan’s RoE is a basic normal bellcurve pattern around the 8% average. In contrast, America produces an average RoE that’s twice as high as Japan’s precisely because it is home to the global RoE champions. America has Superstars and dreams of extraordinary success; Japan has many proud variations of Average and 普通.

I am first-in-line to defend Japan’s system and argue that a “winner-takes-all” outcome is not a socio-economic system we should aspire to. However, there is absolutely no question that in the real world of global investment, capital allocation, and innovation Japan’s inability to produce high return corporate superstars is why Japan’s economy in general, Japanese capital markets in particular have become less relevant for global investors, corporate leaders, and global public policy makers. To be blunt: Japan does not attract the “best and brightest”.

True in sports too. Japan’s best soccer players are now competing in the Bundesliga, and Japan’s best baseball players have an amazing impact in the U.S. Majors Leagues, definitely pulling up the average: the athletic and commercial revival of US Baseball owes much to “Showtime” Shohei Otani, Ichiro Suzuki, and “Godzilla” Hideki Matsui; and, closer to my heart, Germany would probably have won the World Cup a couple of months ago (rather than being kicked-out in the round-robins) if two- or three of the Japanese Bundesliga players had been on the German team….

2) Japan does not pay its workers

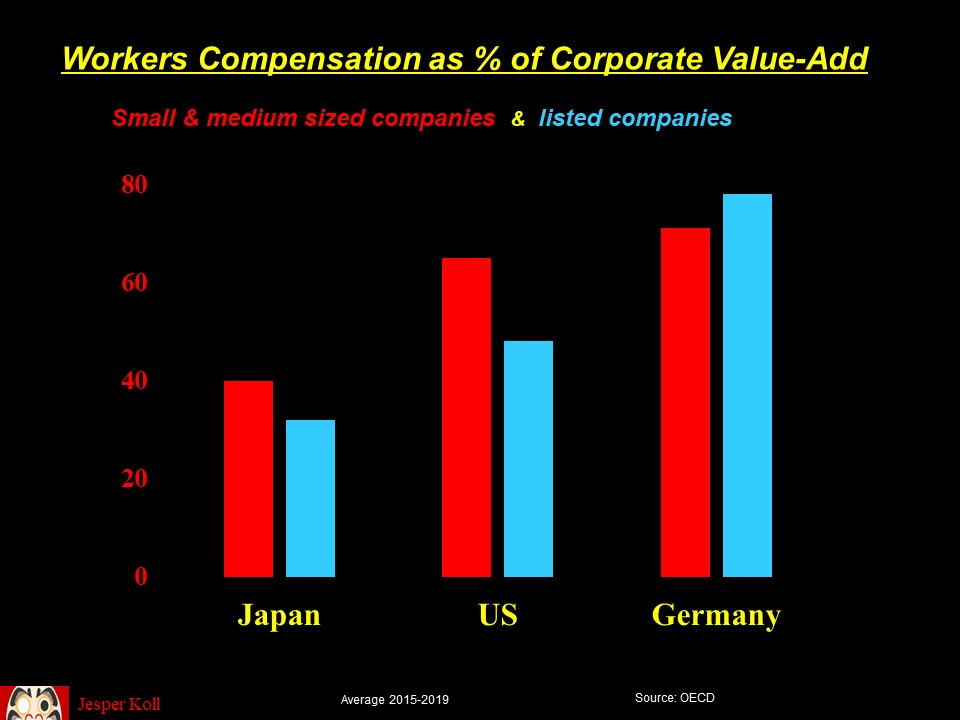

Japan is the undisputed global champion in not paying its employees: workers compensation as a percentage of corporate value-add is lowest in Japan amongst all the OECD countries; and this is true for both the big, globally competitive listed companies and the predominantly domestic small & medium sized ones.

The direct link between low employee compensation and low consumption is an obvious and important one to make - particularly right now when Japan is in the midst of the “Shunto” annual spring wage negotiations. But note that Germany, which boasts the highest payout to workers amongst OECD countries, is hardly known for its consumer-spending-led economy. There is much that happens between getting paid and spending — taxes, debt repayment, access to credit, inflation expectations etc. (see a previous post, “Japan’s Savings Imperative” here ).

All I’m trying to say here is that stingy corporate leaders are not the only ones to blame for Japan’s low propensity to consume.

Still, you cannot spend what you don’t get (and bankers won’t lend to you if they know you won’t get more in the future either….).

The good news: given corporate Japan’s massive cash hoarding, paying employees more does not have to be a zero sum game. In fact, tapping into “lazy balance sheets” to pay for your most important productive asset, your employees, is poised to raise capital efficiency. And, with a little luck, you’ll be able to attract future superstars….

3) Japan is rich but household wealth is not really growing

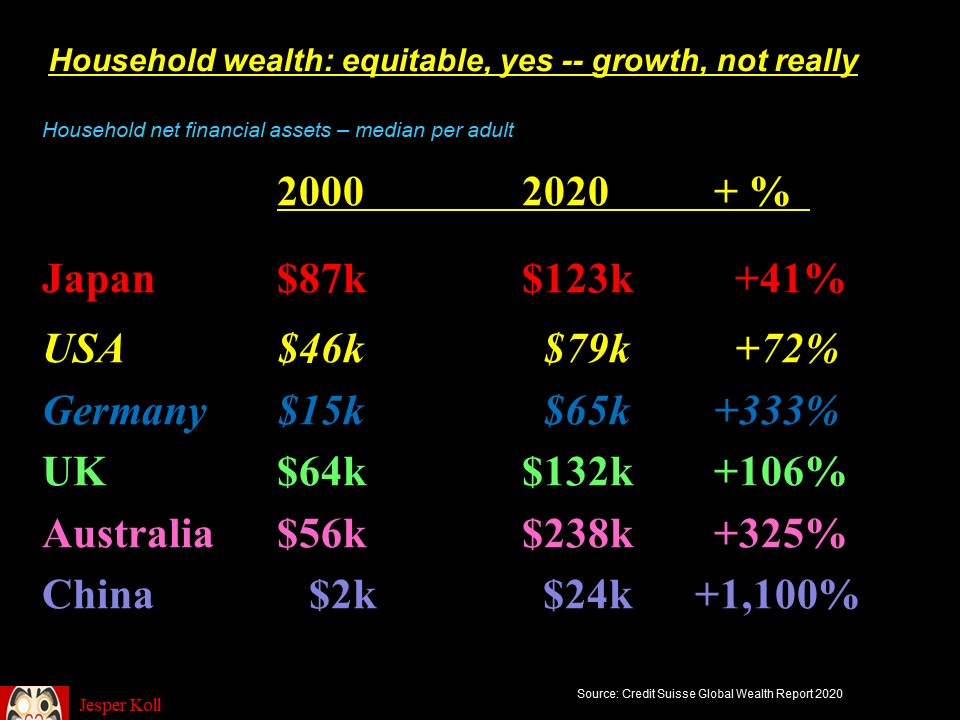

Japan is very rich, has been the world’s largest net creditor country for the past 31 years, and is the envy of the world for its equitable wealth distribution. (see the previous post, “What is Japan’s economy is really good at?” here )

Yet Japan is relatively bad at actually creating new wealth and prosperity for its people: over the past twenty years, household sector wealth has grown by just 41%, while it grew 72% in America, 333% in Germany, and over 1000% in China.

All said, a consistent picture emerges: Japan has a tremendous stock of wealth and very equitable distribution; but is not really good at creating new flow, i.e. growth.

Importantly, this lack of growth, is NOT because of a declining population, but because of ill-defined incentives: companies opt to hoard cash rather than invest in their business or their primary productive assets, employees; potential superstars and innovators are better off playing for the global competition than waiting patiently for their turn at home.

The optimist view:

Japan is now at a once-in-a-generation inflection point. Fast Retailing is raising pay by 40%, a first hike in practically 20-years; and they are doing so to align with global standards and because they know the domestic “war for talent” will only get worse from here. NTT is braking ranks, introducing pay-for-performance and merit-based promotion. Imagine what this will do to the number five or number ten player in the industry?

Yes, Japan faces a tremendous re-allocation challenge. The gap between high-performers and low-performers will probably rise. Japan will give up a little bit of the “good” outlined in the previous post to my Davos-bound friend to correct the “bad” outlined to my concerned technocrat friend in this one. I remain a Japan optimist because I trust entrepreneurs and next-generation business leaders will work hard to correct the bad while the technocrats will keep working overtime to preserve the good.

Thank you for reading. As always, comments welcome. Many cheers, today from snowy Kyoto ;-j

Presumably a lot of the increase in net financial assets in countries such as Australia is due to house prices growing faster than mortgage liabilities. I wouldn't consider that kind of growth in household wealth to be very good, I prefer Japan's housing market - easier to enter, and more equitable!

I love these posts, about a country that I adore (as a visitor, of course). Thank you for writing these.